VIDEO: Rethink Poverty

VIDEO: Storytelling Trip to Burundi

VIDEO: Wet Markets vs Grocery Stores

PHOTOS

JOURNAL

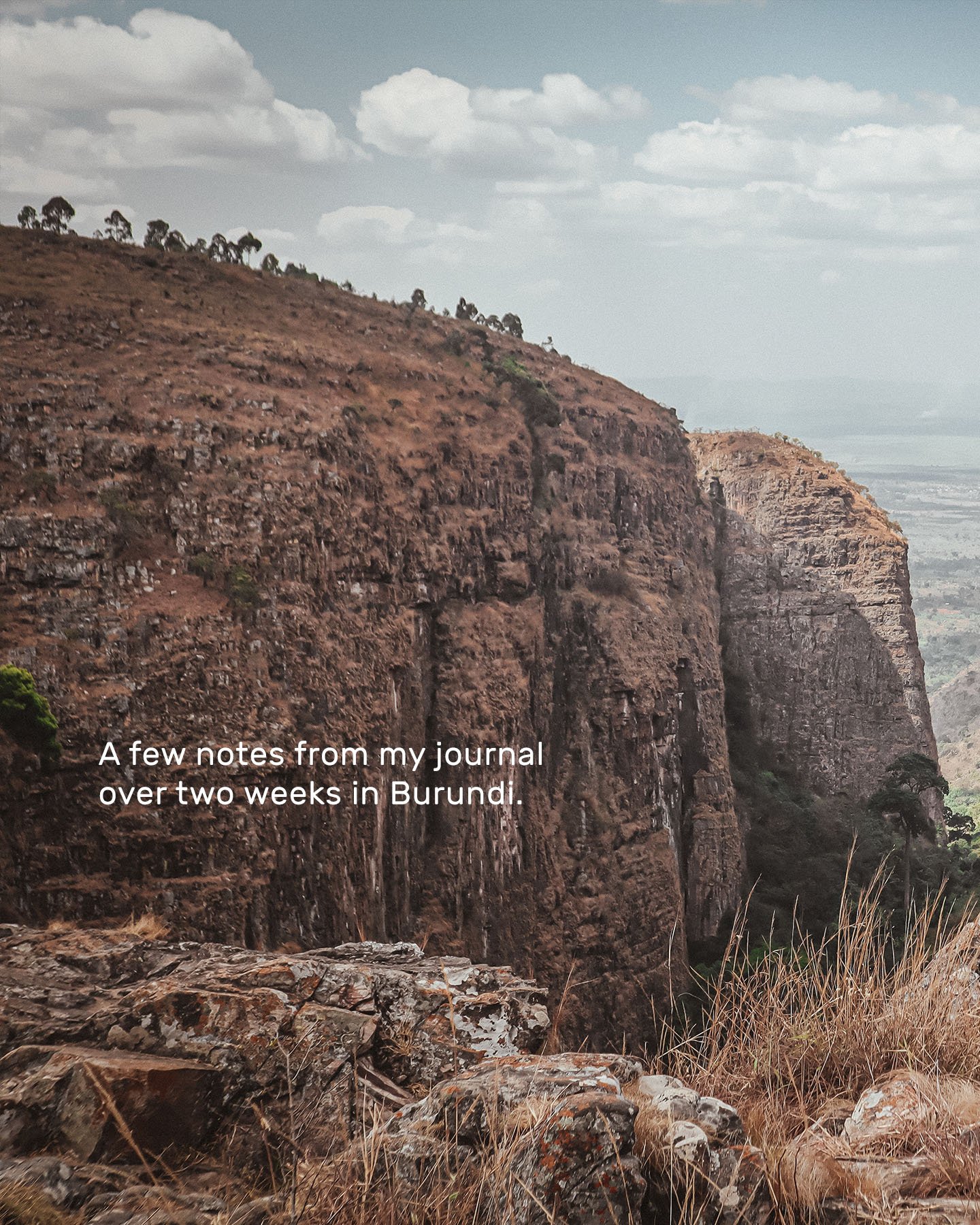

THIS IS BURUNDI

Burundi is drumbeats, mosquito nets, and pineapples.

Burundi is plates of ugali, bananas, pomme frites, meaty chicken, and lengalenga.

Burundi is that baseball score that manages to find your phone after driving for days without reception.

Burundi is amahoro.

Burundi is horned cattle.

Burundi is walking with sensitivity towards its recent history of tumultuous events.

Burundi are bottles of Primus, yellow jerry cans, and plastic discs turned into kids’ toys.

Burundi is the curiosity of children, the bright pattern of women’s dresses.

Burundi is meeting a man who used to eat once a day now feeding all five of his kids three solid meals.

Burundi is families, friends, and new friends taking selfies at the foot of a waterfall.

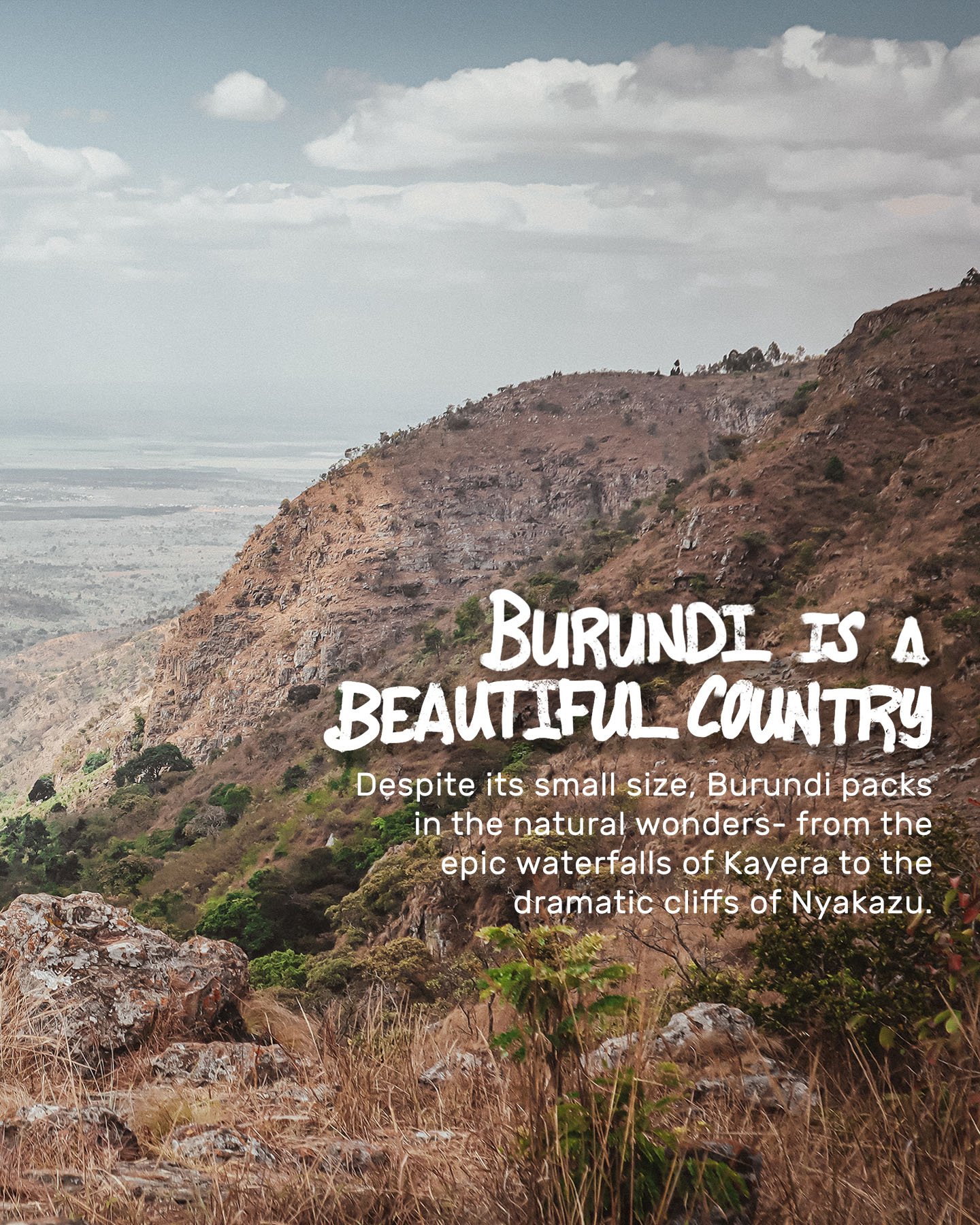

GEOGRAPHIC WAKANDA

Whenever I tell people about the time I got to spend in Burundi, the most common reaction I get is this:

Cool. Where is that??

Here’s my geography lesson for ya. Go put on Black Panther. Play that opening scene with Sterling K. Brown reading the legend of Wakanda as a bedtime story. Take note of where in Africa they zoom in and out of. Small country, east of Lake Tanganyika.

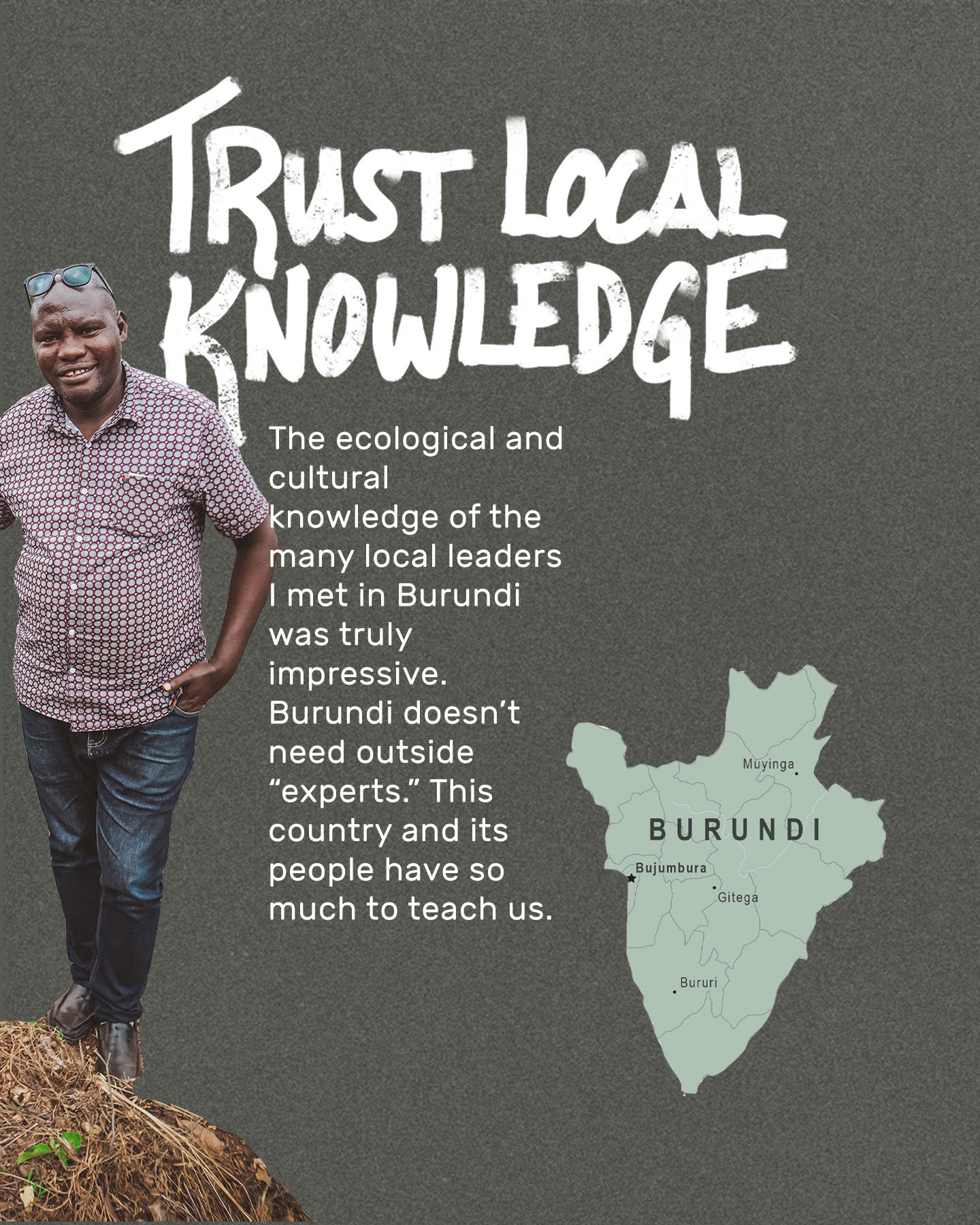

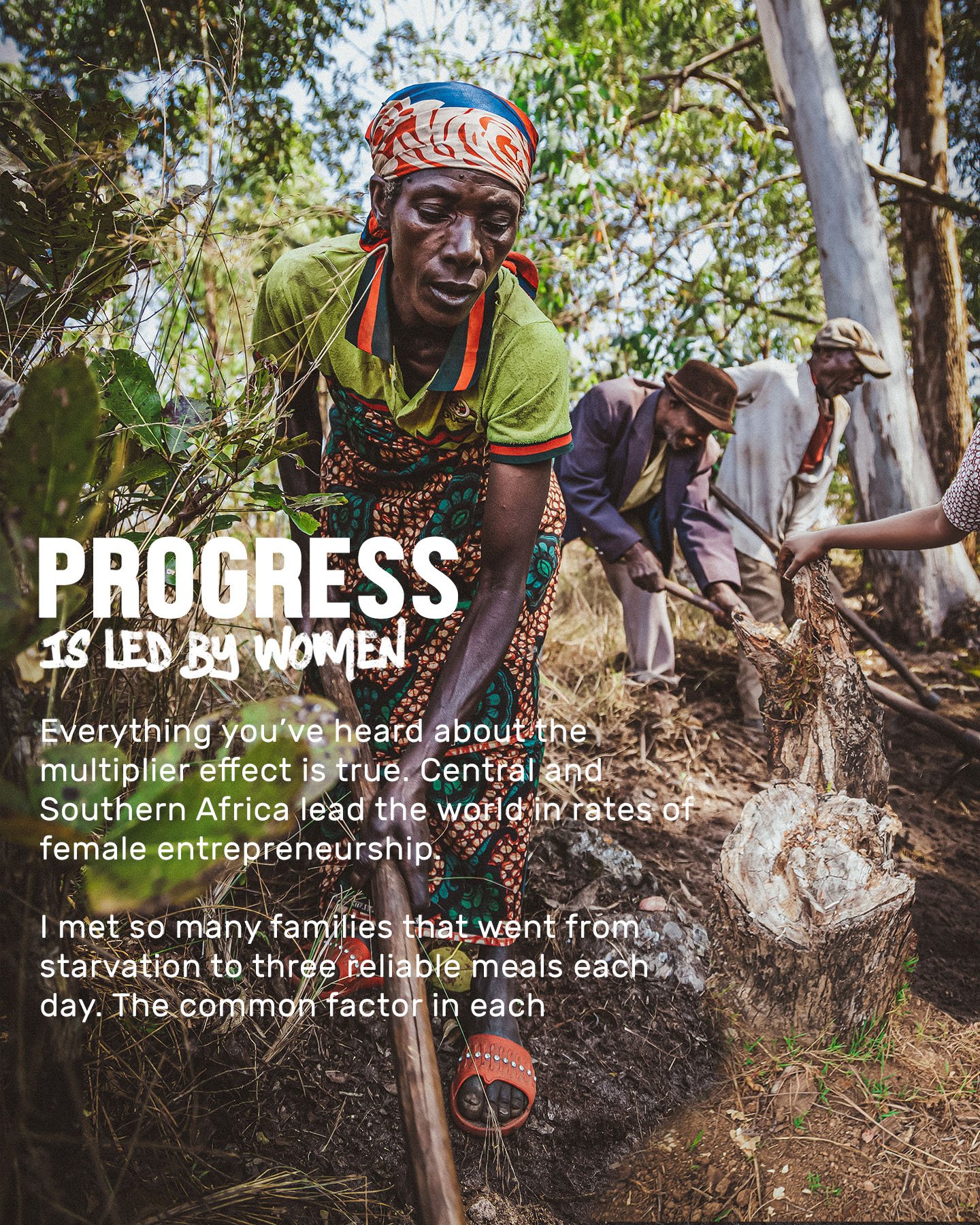

I learned so much from spending two weeks in Burundi, and geography was only a small portion of it. It’s a gorgeous country, underestimated due to its struggles with hunger and conflict. But there are so many local leaders, women especially, who are driving the country forward while working to preserve its nature and culture.

FIELD NOTES FROM BURUNDI

KEPT OUT OF CONGO

Three days before my trip to Africa, I got an urgent sounding call.

*We’ve got a situation*

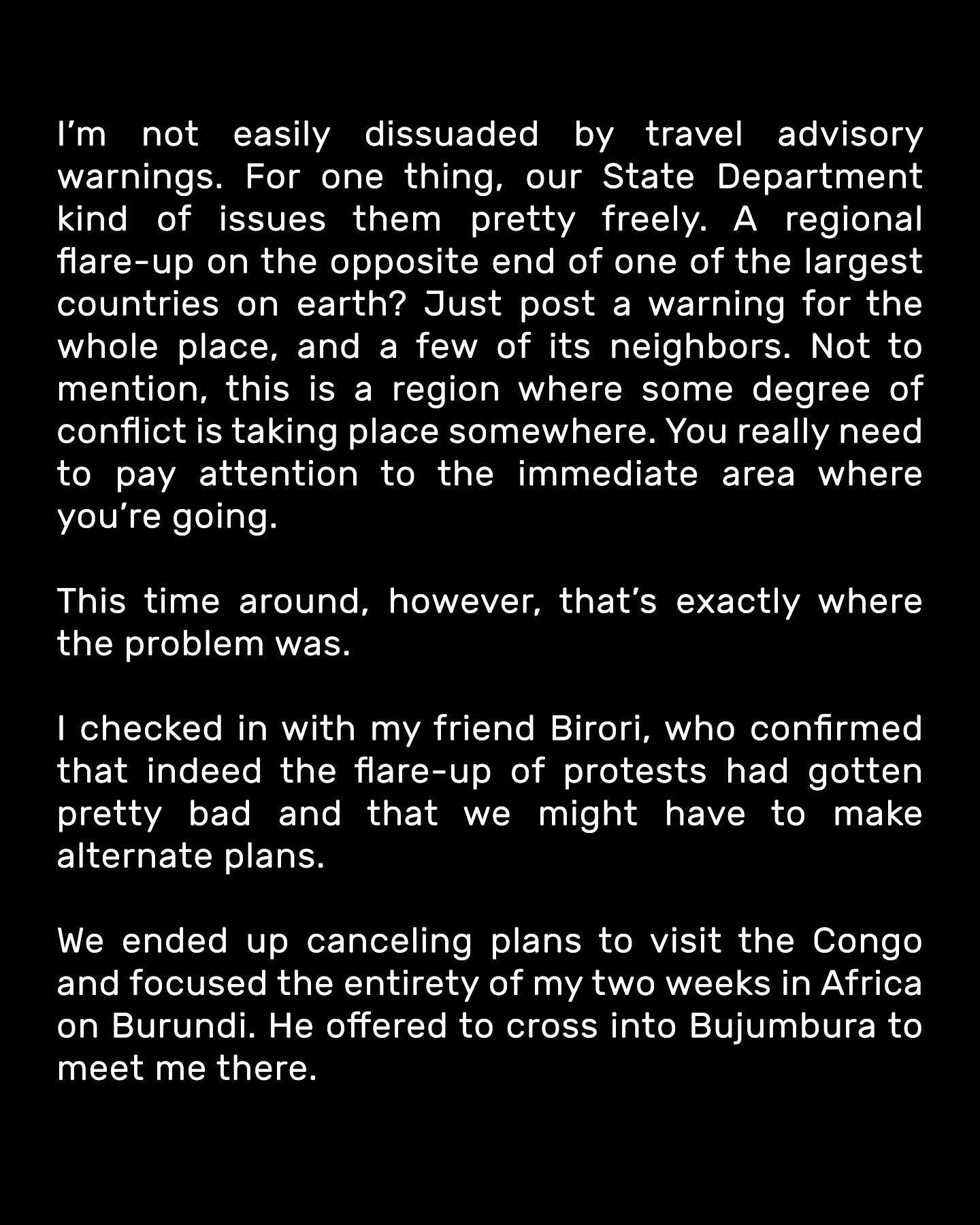

I’m not easily dissuaded by travel advisory warnings. For one thing, our State Department kind of issues them pretty freely. A regional flare-up on the opposite end of one of the largest countries on earth? Just post a warning for the whole place, and a few of its neighbors. Not to mention, this is a region where some degree of conflict is taking place somewhere. You really need to pay attention to the immediate area where you’re going.

This time around, however, that’s exactly where the problem was.

I checked in with my friend Birori, who confirmed that indeed the flare-up of protests had gotten pretty bad and that we might have to make alternate plans.

We ended up canceling plans to visit the Congo and focused the entirety of my two weeks in Africa on Burundi. He offered to cross into Bujumbura to meet me there.

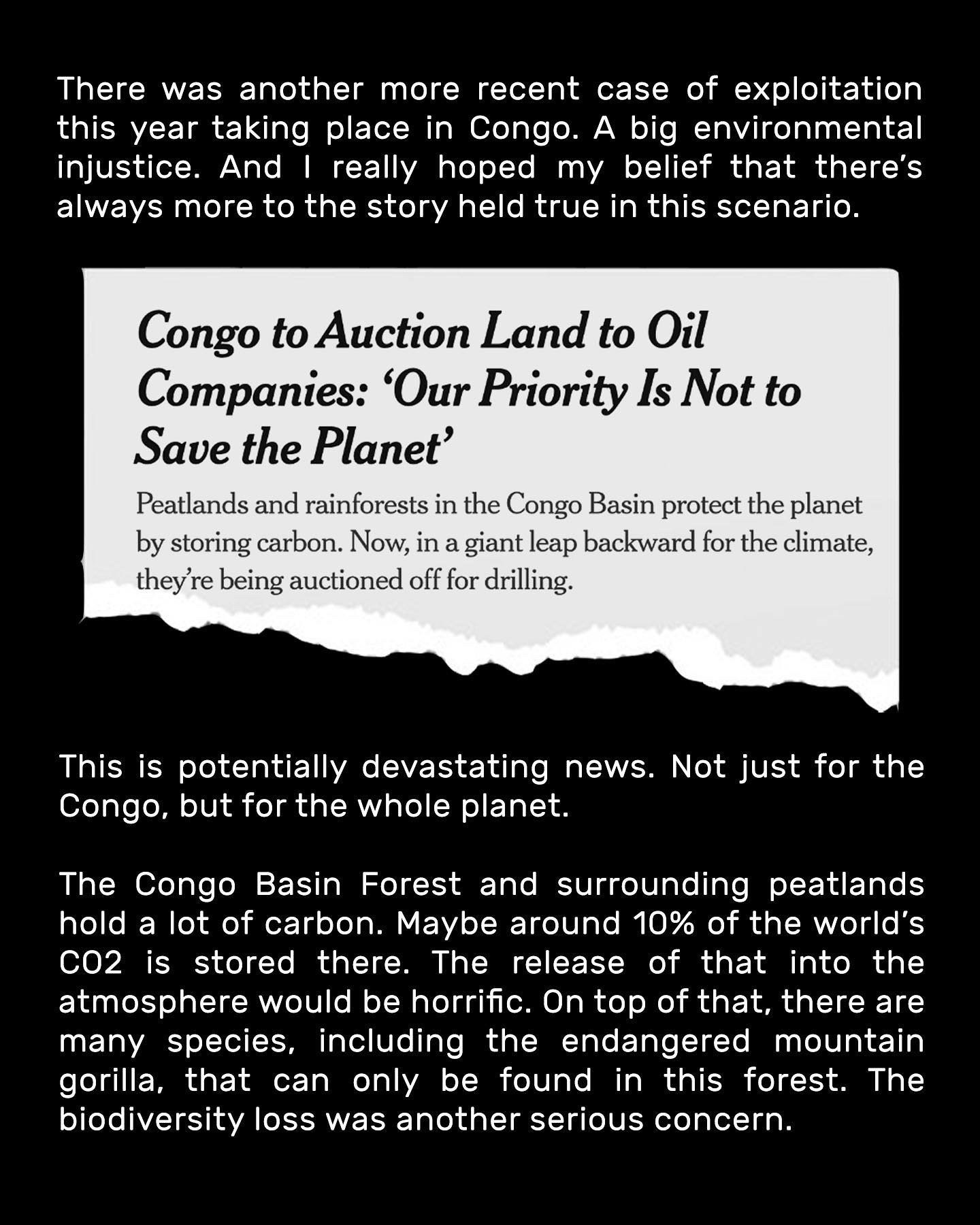

The worst environmental news I heard this year was most likely the announcement that the Congo Basin Rainforest would be open for drilling. It’s a rainforest that holds about a tenth of the earth’s carbon, and hosts so many species that can’t be found elsewhere. That seemed like a huge blow to climate and biodiversity.

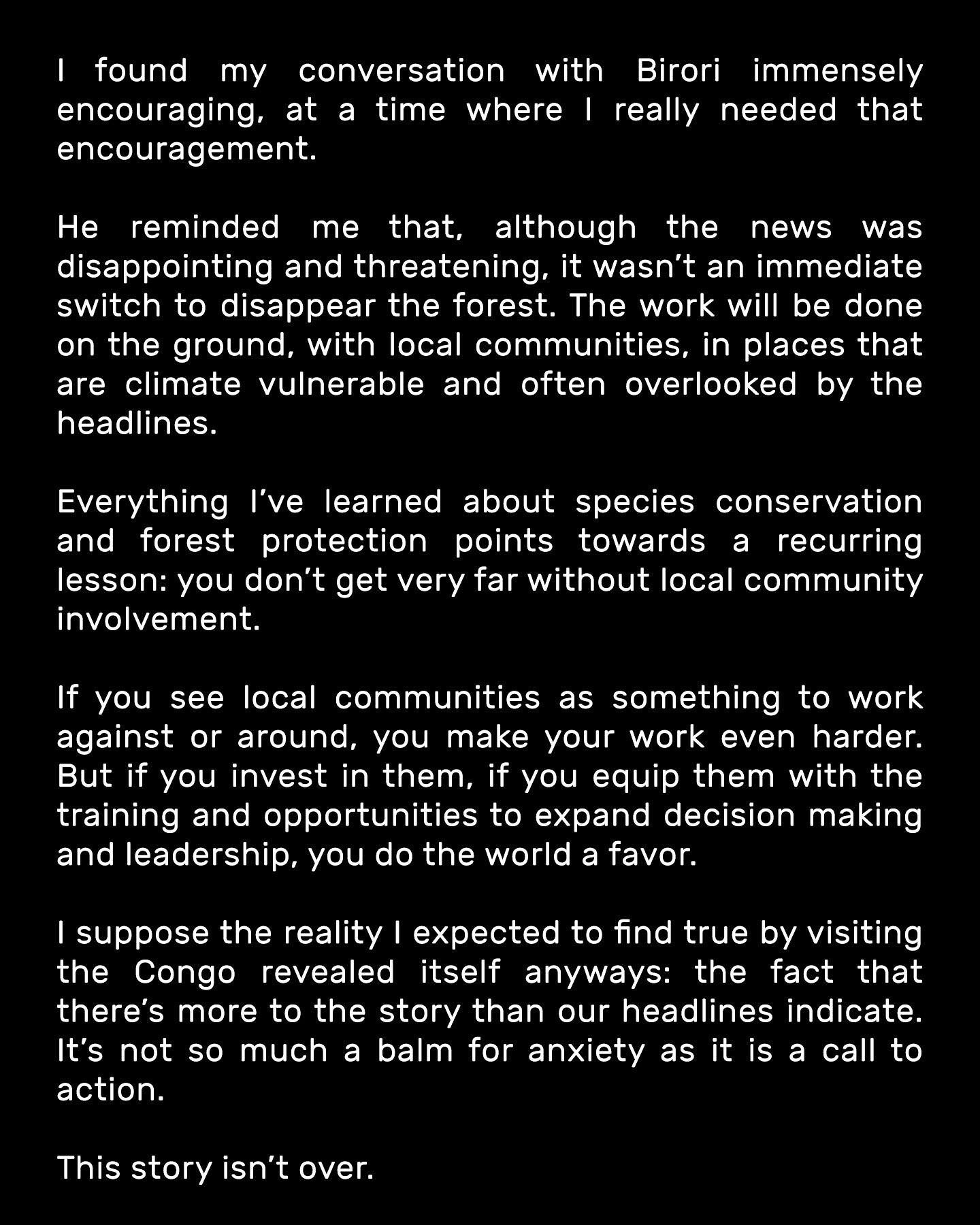

Getting to talk to Birori, who promotes ecosystem restoration through working directly with communities was a valuable reminder for me.

Even though his team was fully aware of how unfortunate the news was, he knew that forest protection is best when local communities own the process.

Hopefully the next time I’m in this part of Africa, a visit to the Congo Basin Rainforest could be in order.

when the trips go wrong

I share a lot of travel stories, and so I should make it known that behind the scenes of just about every trip I’ve taken lately is something that did not go at all according to plan.

My trip to Burundi was nearly derailed because back when I went, they required a negative covid test 48 hours before arrival… but the journey there is 36 hours, and when you add sleep time, I just had to take a chance flight to New York hoping the results came in while on the first leg of my flight.

I laid out an ambitious itinerary for my Ethiopia visit. Everything happened, except in the reverse order I planned. A death in one of the sites we planned to film meant we had to do everything backwards.

I’m also more conscious now of how much energy these trips take and realize that planning a buffer day to rest and feel alive again before diving in is a necessity.

One of the skills I value, not just out of travel but out of life, is adaptability. I’ve had a number of unexpected things happen in life that derailed expectations, and I wonder if that’s why I’m drawn to things like improv or even Chopped. Looking at a basket of weird ingredients and thinking, let’s see what we can make out of this resonates at some deep level.

These days, I go into trips realizing that every plan can go awry, but in spite of that, it’s still helpful to make the plans. Valuable. Make them down to every last detail, then hold them loosely. Somehow, that’s what works best.

DEFORESTATION IN BURUNDI

So often, when I think about deforestation, I think of greedy businesspeople with fat cigars and gold chains pointing towards the Amazon while dreaming of their next swim through a vault of cash. But that’s not always the case.

At least a third of the time… if not more… deforestation is driven by ordinary people trying to put food on the table for their families. In Burundi, charcoal was the most visible example of how this works.

Trees can be made into charcoal.

Charcoal brings in quick cash.

But the loss of trees drives soil erosion.

Soil erosion leads to food insecurity.

It’s a vicious cycle.

That’s why I don’t see climate action and development against poverty as separate streams. If you don’t pay attention to both, efforts only go so far.

I tell a lot of success stories of people working on climate solutions and resilience, but Antwan’s isn’t one of those stories. I met him because I saw he was burning trees to turn into charcoal and I saw the smoke from the roadside.

Every three years he cuts down all the trees around him for more charcoal.

I share this encounter though, because his reasons for doing so were simply to feed his family. This was the only activity he’s found that could bring in adequate cash when needed. It was a reminder to me that not everybody involved in deforestation is a greedy honcho with a cigar and gold chain. They’re out there, I’m sure. But the more we can humanize each other and understand causes, effects, and motivations, the more effective our solutions will be.

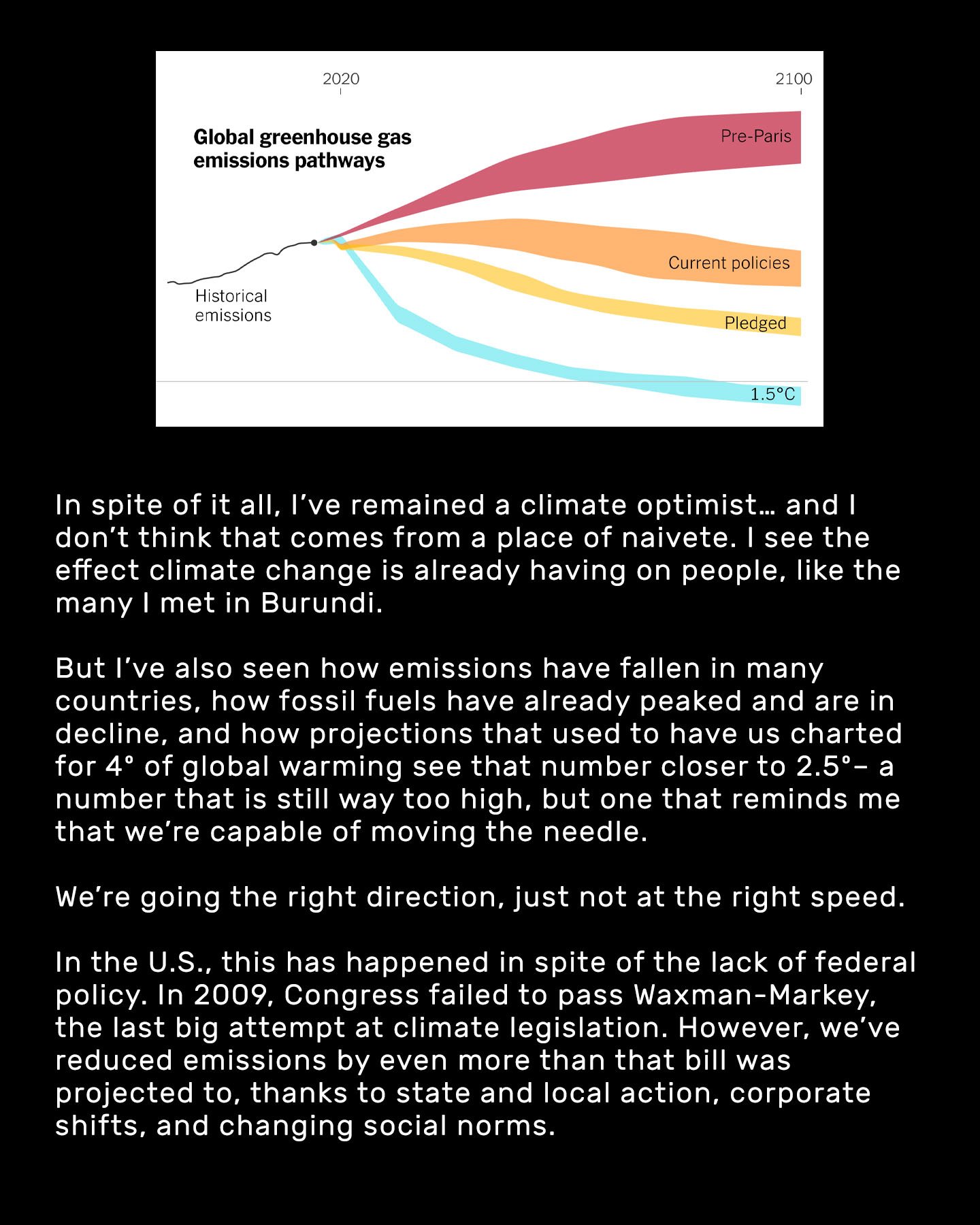

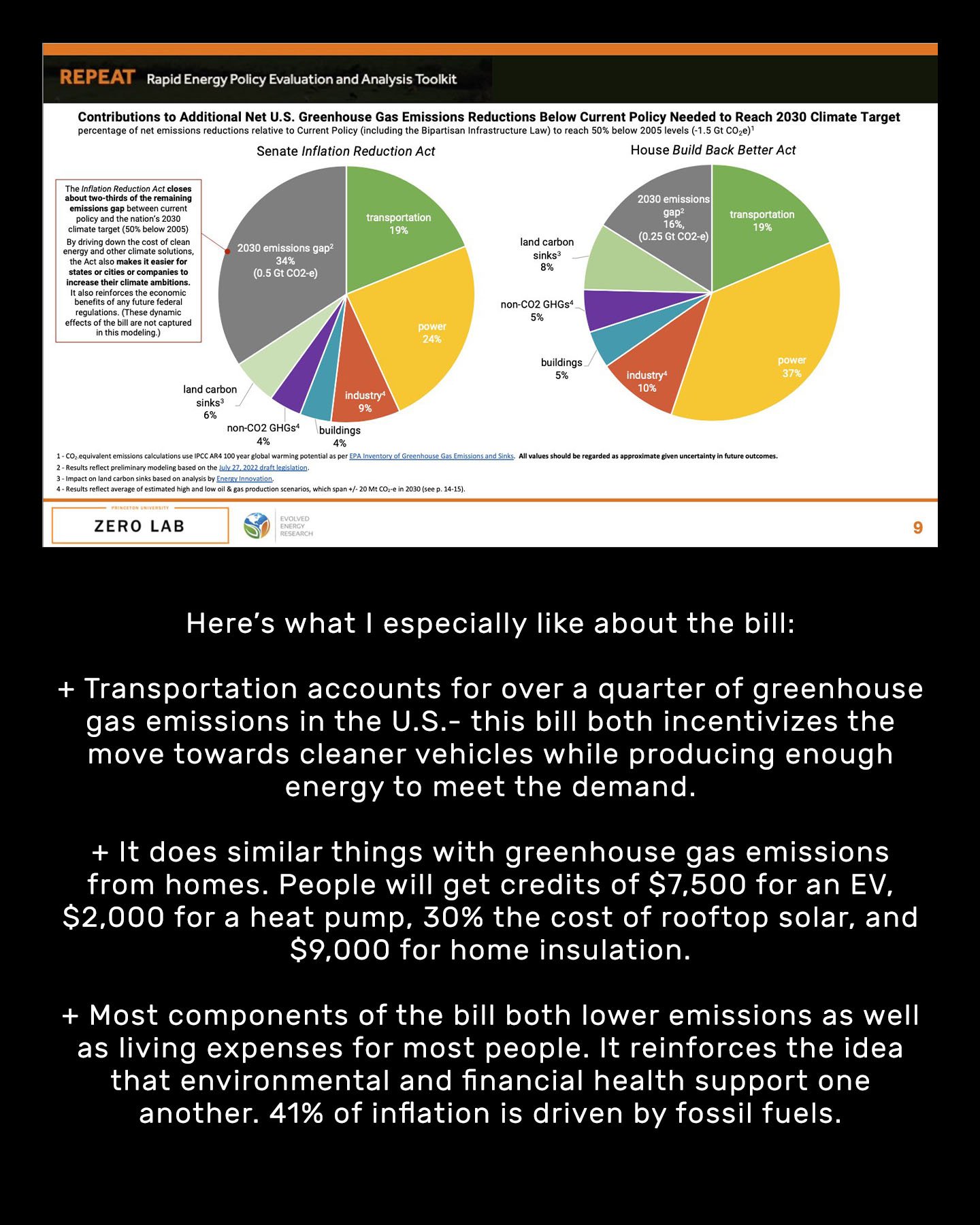

climate legislation

A PLACE IN THE WORLD

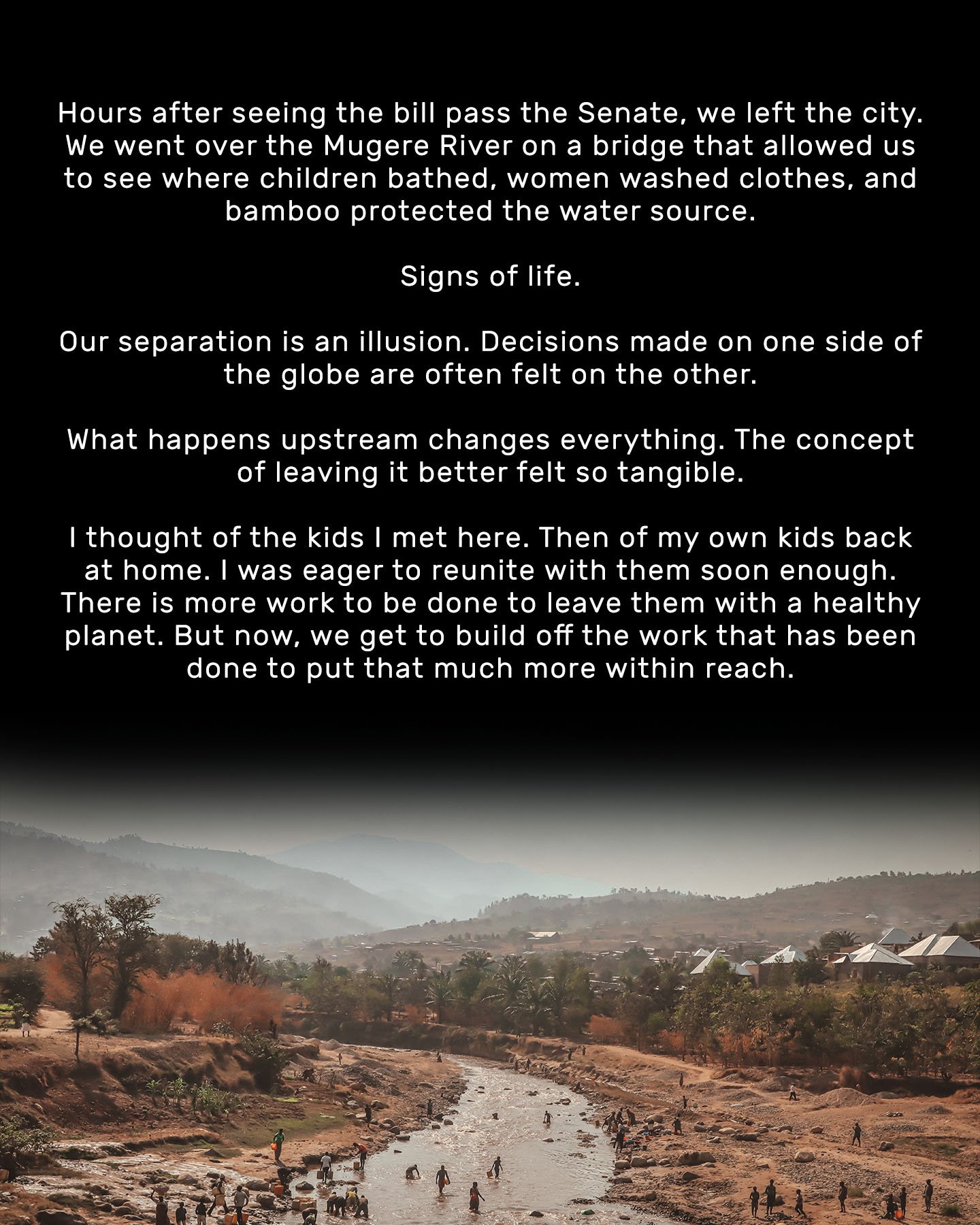

Walking into Mugere, a young girl met us along the way to help us make our way up the hill and towards the family home. It was about an hour of hiking, including over some parts that required walking on planks of wood that bridged gaps in the road.

Daniela made sure to take me by the hand and help me get across the whole thing. I think we ended up holding hands for nearly the entire hour long hike.

Her parents, Esperance and Deo, would turn out to be the couple we interviewed for our video.

With Esperance. Her arm was lost during Burundi’s Civil War.

Development Looks Different Everywhere

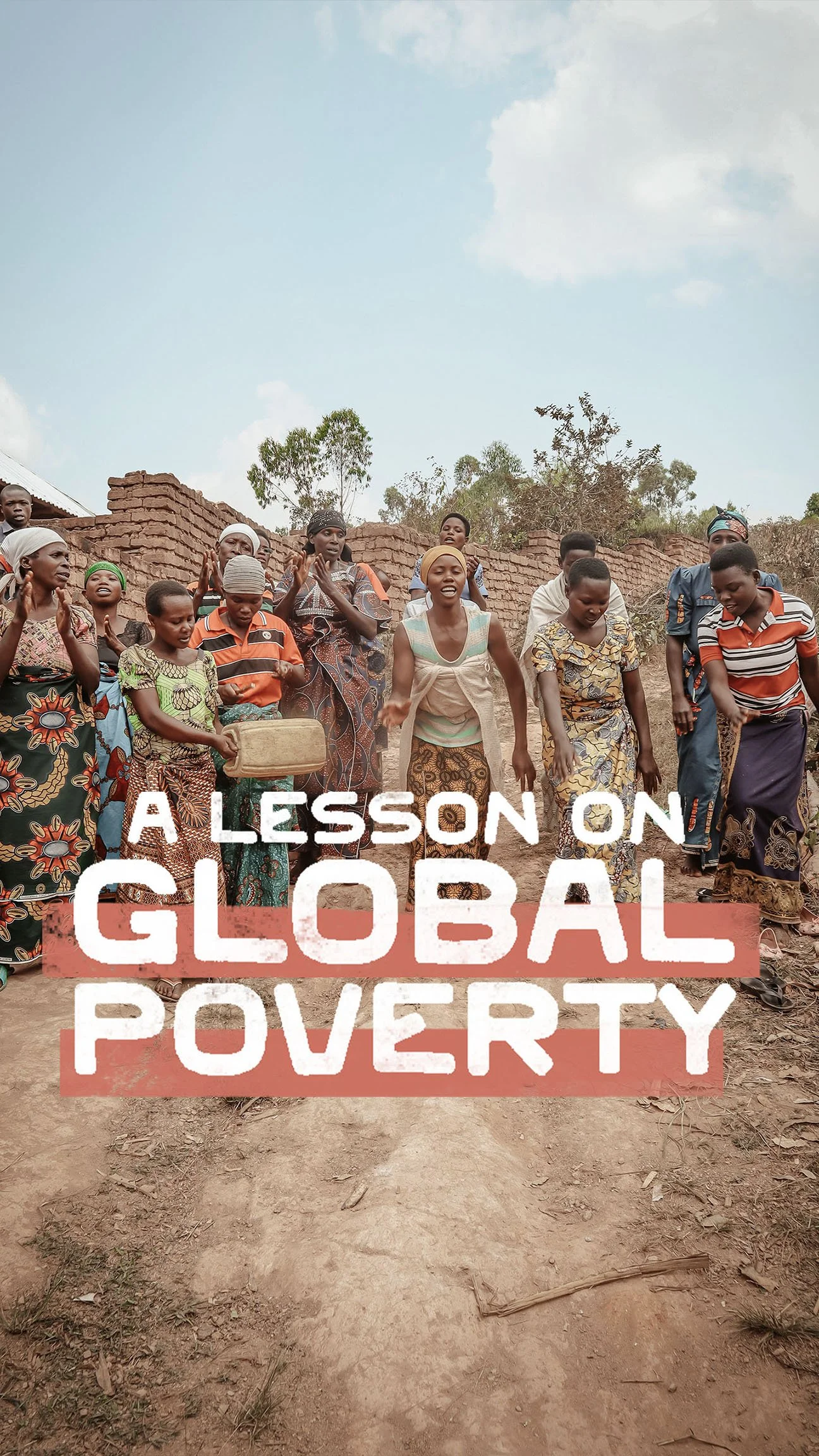

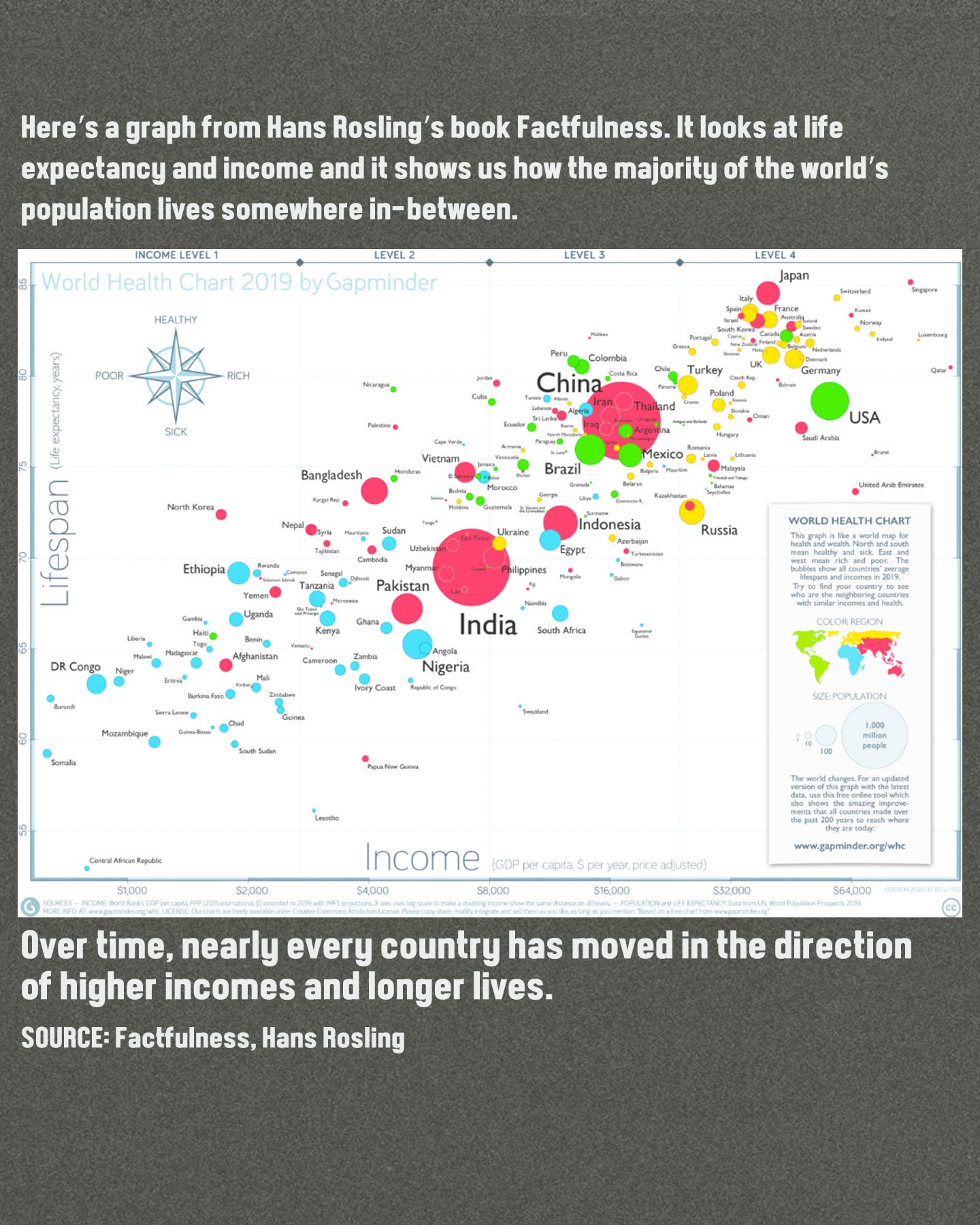

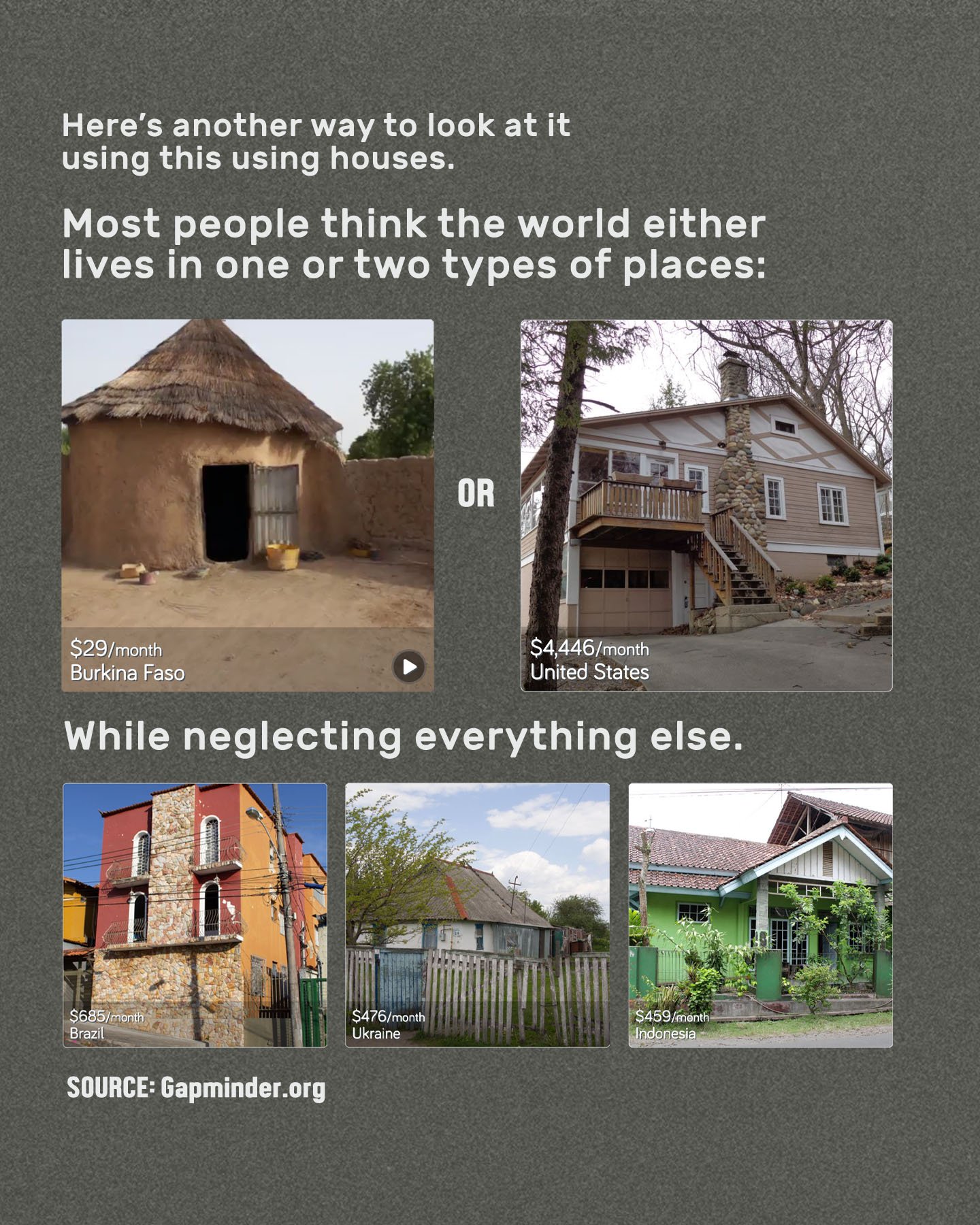

RETHINKING POVERTY

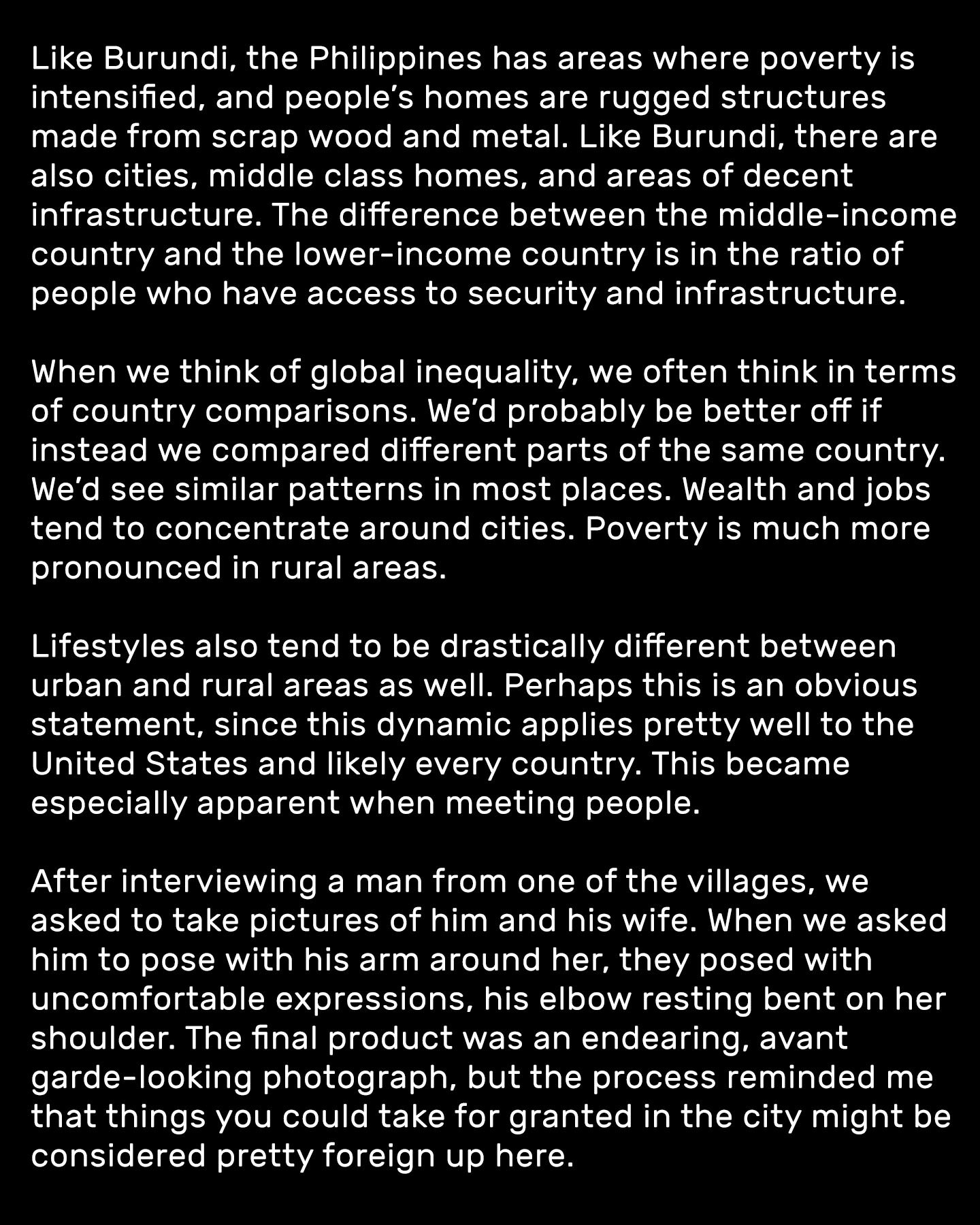

A random pet peeve of mine is when people talk about middle income countries like the Philippines, India, or Dominican Republic as though they were one of the poorest countries in the world. In fact, they’re squarely in the middle when you map things out.

Why? I mean, yes, there are parts of those countries, especially in the rural areas, where you can still find pretty difficult living conditions and steep poverty, but when we make it seem like the entire country might as well be on par with one of the twenty lowest income countries in the world, we really flatten the story of a lot of good that has happened in the world.

(And yeah, I also don’t like the way we talk about lowest-income 20 countries, even where poverty is widespread and extreme, but that’s for another time.)

Over the course of my lifetime, the majority of the world has seen significant improvements to their living conditions. Most have moved from poverty into more of a middle state, and perhaps if more people saw the world through that lens, we’d be less tempted to think of poverty as an inevitability.

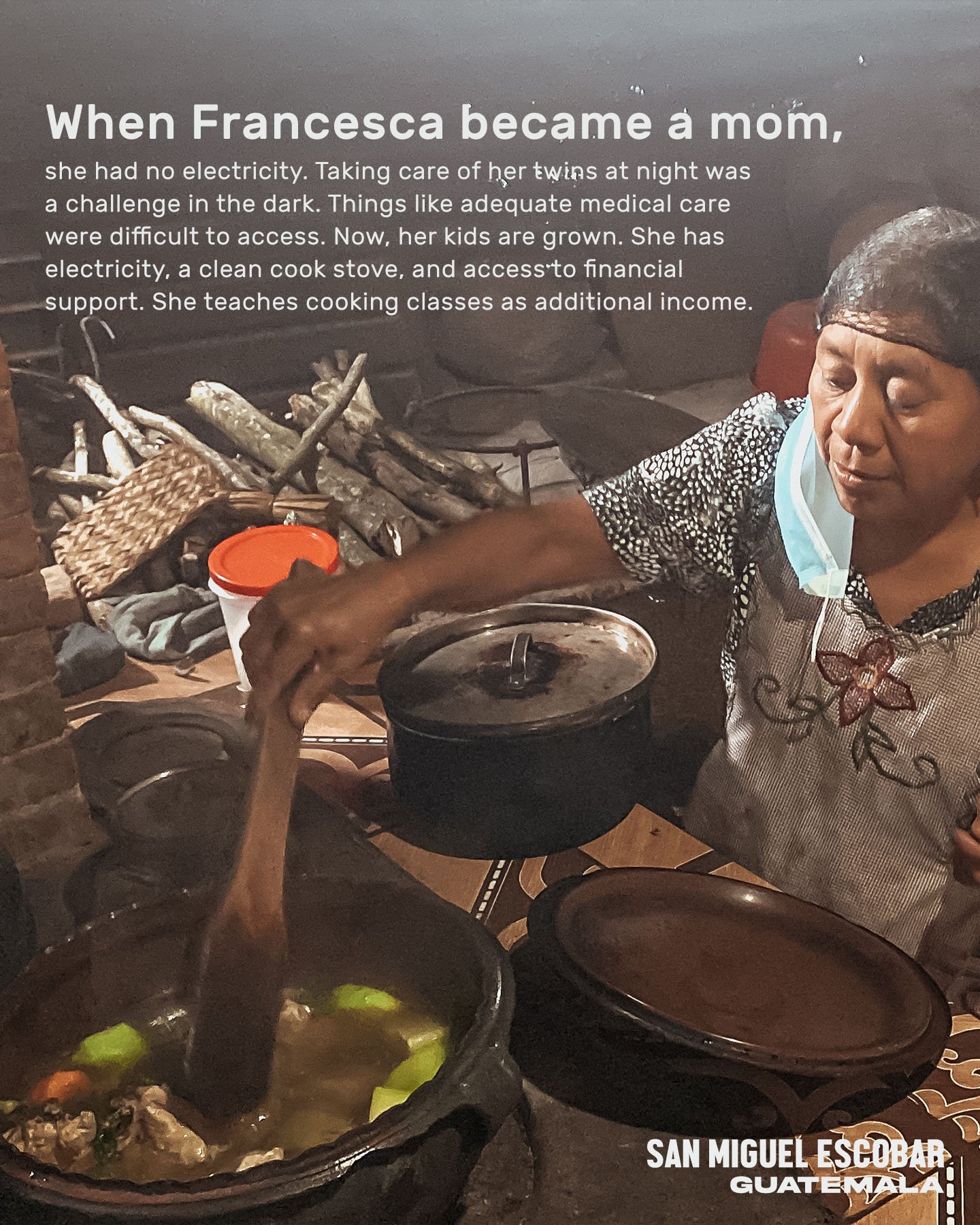

Poverty is a complex thing to talk about.

There are so many stereotypes associated with it, so many examples of people depicting poverty in ways that diminish the humanity of people with that experience.

And yet, it’s a reality for so many people and a root cause of so many problems we need to talk about it. So many people have shared with me their challenges while living in poverty because they want other people to know about them. Sensationalizing poverty is not ethical storytelling, but neither is omitting it entirely, or romanticizing it.

You’ve got to be humble about this, because no amount of research or travel can give you the full insight that comes with lived experience.

Remember that poverty isn’t a fixed condition. People, communities, even entire countries have shown us that living with insufficient resources is not an inevitable condition.

Put poverty in its proper context. Pay attention to where issues like climate change or colonialism have created the conditions for poverty or insecurity. Places don’t have widespread poverty just because.

But most of all, don’t lose sight of the human being in the story. Don’t conflate someone’s personhood with their problems.

““I assure you, because I have met and talked with people who live on every level… the distinctions are crucial. People living in extreme poverty on Level 1 know very well how much better life would be if they could move from $1 a day to $4 a day, not to mention $16 a day. People who have to walk everywhere on bare feet know how a bicycle would save them tons of time and effort and speed them to the market in town, and to better health and wealth.””

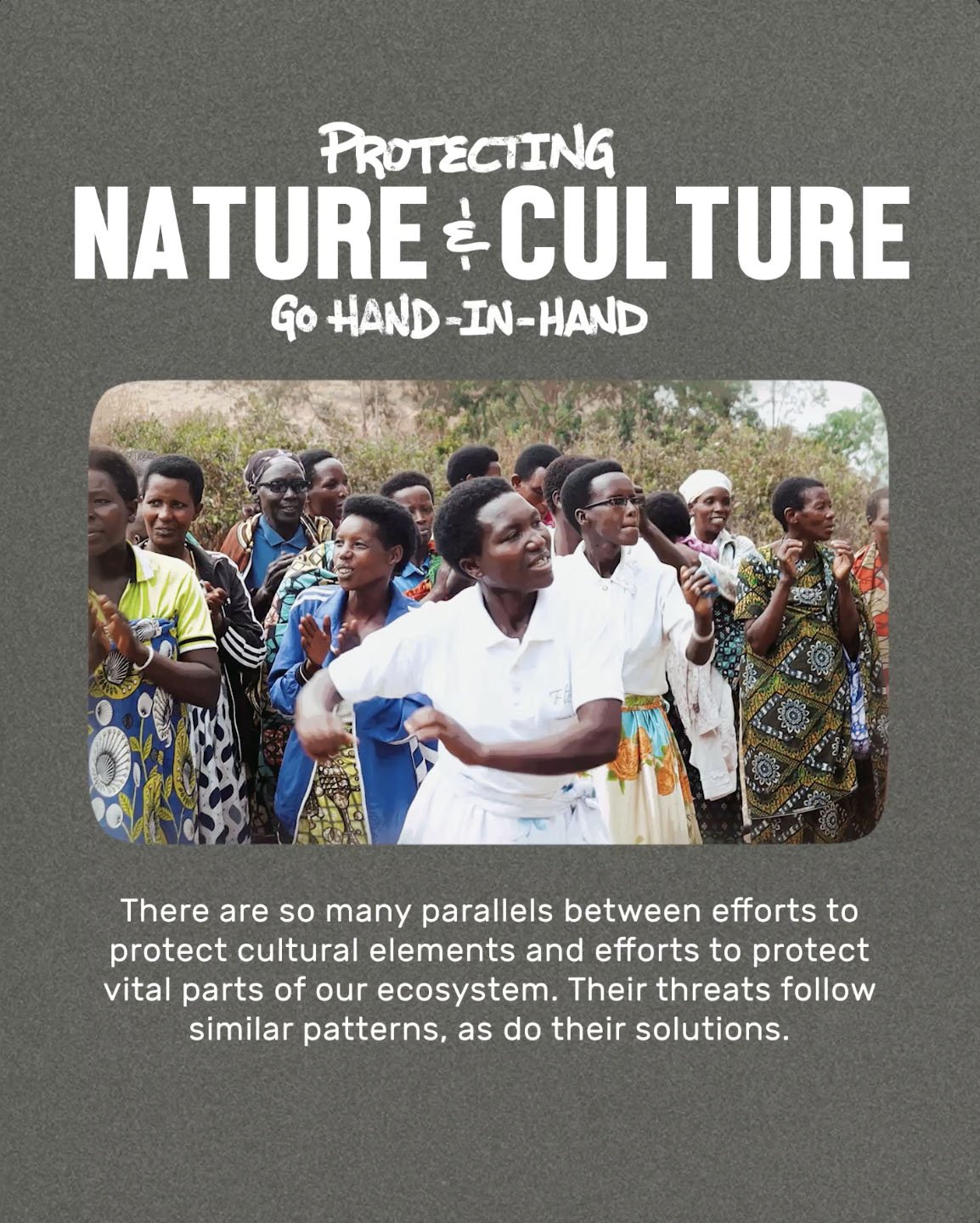

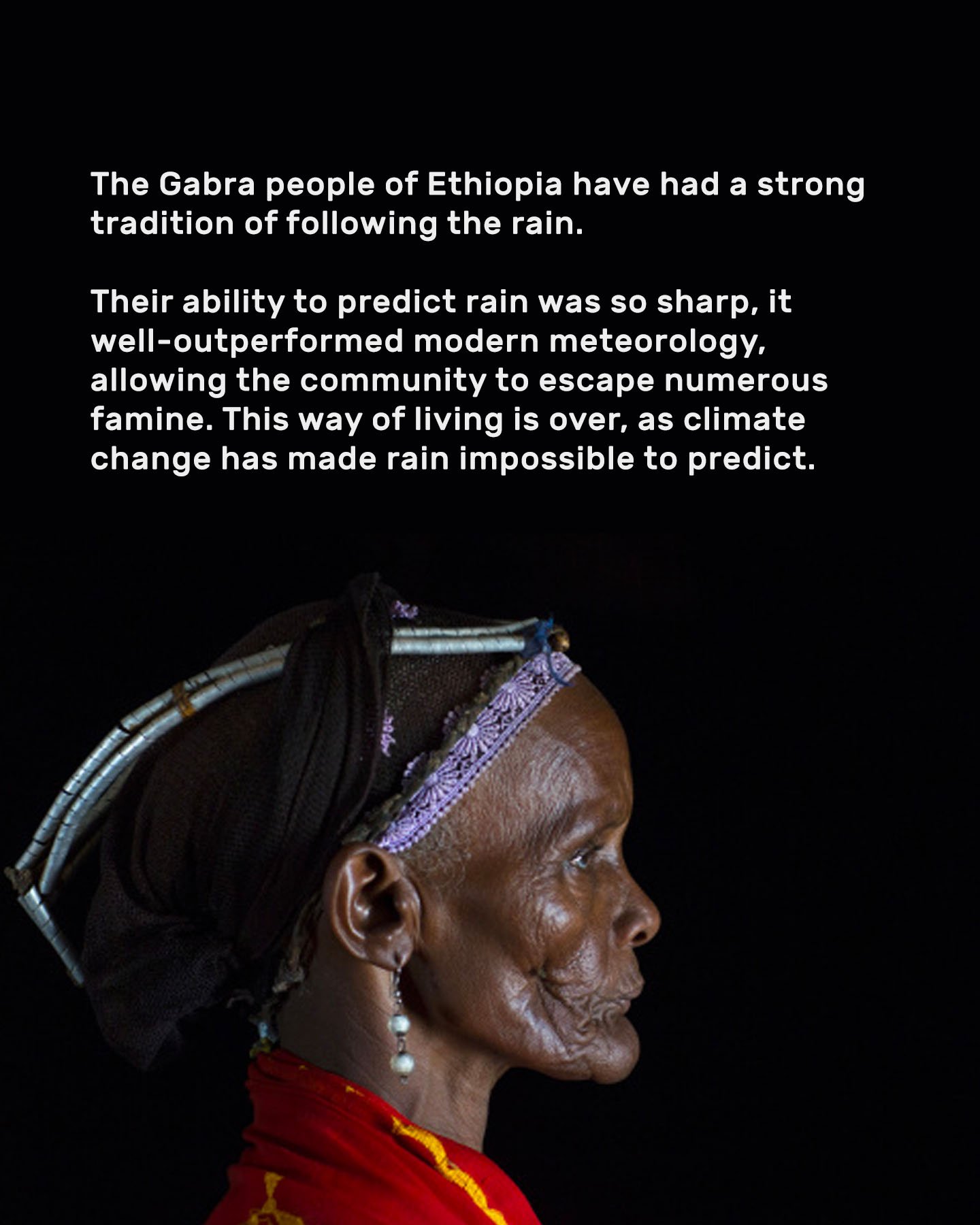

WHAT’S GOOD FOR NATURE IS GOOD FOR CULTURE

What’s good for nature is good for culture.

And vice versa.

In Burundi, I was greeted by multiple Ingoma performances… dances set to the thundering royal drumbeats that carried throughout a hillside.

Then my friends showed me the tree the drums were made from. Cordia Africana. AKA Sudanese Teakwood. An endangered tree, whose wood is irreplaceable when it comes to getting the thundering sound just right.

In Alaska, I became intrigued and invested in native languages that were down to a few dozen speakers.

I found a map that showed the correlation between places where languages were going extinct and places where wildlife was going extinct.

And it all became clear.

Countless cultural traditions are at risk as habitats are threatened. But efforts to protect nature can help preserve culture. And promoting the agency of indigenous groups also has benefits to nature.

What’s good for nature is good for culture.

INGOMA

Just imagine it’s late in the day. The daylight is almost burnt up, except for that last orange glow. You hear an elongated shout, then some thumping. Then it explodes into a rhythm.

The drummers emerge. They’re in line. But some cut to the front. And others follow in a pattern. One moves to the center to leap.

Burundi’s the country of big beats, largely because of their tradition of ingoma drumming.

These drums were used in royal ceremonies, like crowning a new ruler or mourning a funeral. Because the drums were made of cordia africana, or Sudanese teakwood, their sound could travel a far distance. Right up close, however, it simply thundered.

Today the big beats are also used to honor and welcome special guests. I kept trying to find out if they were ever used for war. It seems possible, but I never found that explicitly stated. The ceremonial reasons were the main priority.

But i do know the sound of those drums is a bigger pump up than any locker room anthem I can think of. If I was an opposing army and heard the way those sounds echoed… game over.

The Opposite of Watching the News

What do you think the opposite of watching the news would be?

I don’t actually like dunking on the news all the time. One of the first things crooked leaders do is make people distrust the media so they can fill the vacuum of information. The press plays a big role in keeping power in check.

That said, news can distort the way you see the world depending on how you look at it. And it’s not necessarily the fault of the anchors you see on screen or the people writing the articles. We shouldn’t expect the news to be a representation of what-the-world-is-like. In fact, if something is “normal” then it isn’t exactly “newsworthy.” It’s healthier to think of the things you see on the news as exceptions to the norm.

This is important, because I often ask my audience how they feel when watching the news and words like depressed and disenfranchised come up a lot. I don’t advocate shutting ourselves off to it, unless that’s really the thing for you in a personal journey. Most of us just need to do a better job remembering that our world primarily consists of ordinary people doing their best to have a good day and do something good for those around them.

SKETCHBOOK

Ingoma

My visit to Burundi took me to a country full of some pretty tall statistical extremes when it comes to things like hunger and insecurity. This part of the map has been in a lot of headlines this week… and not for especially great reasons.

However, you and I know that those numbers and headlines tell a reductive version of the story and that there’s always a lot more… more that you can’t really start to grasp without some proximity.

It’s harder to reduce people into a simple statistic when you’re up close. And that’s why I’ve been wanting to make this trip happen for years.

REELS

1 Burundi

2 Mariam’s Convenience

3 Three Meals a Day

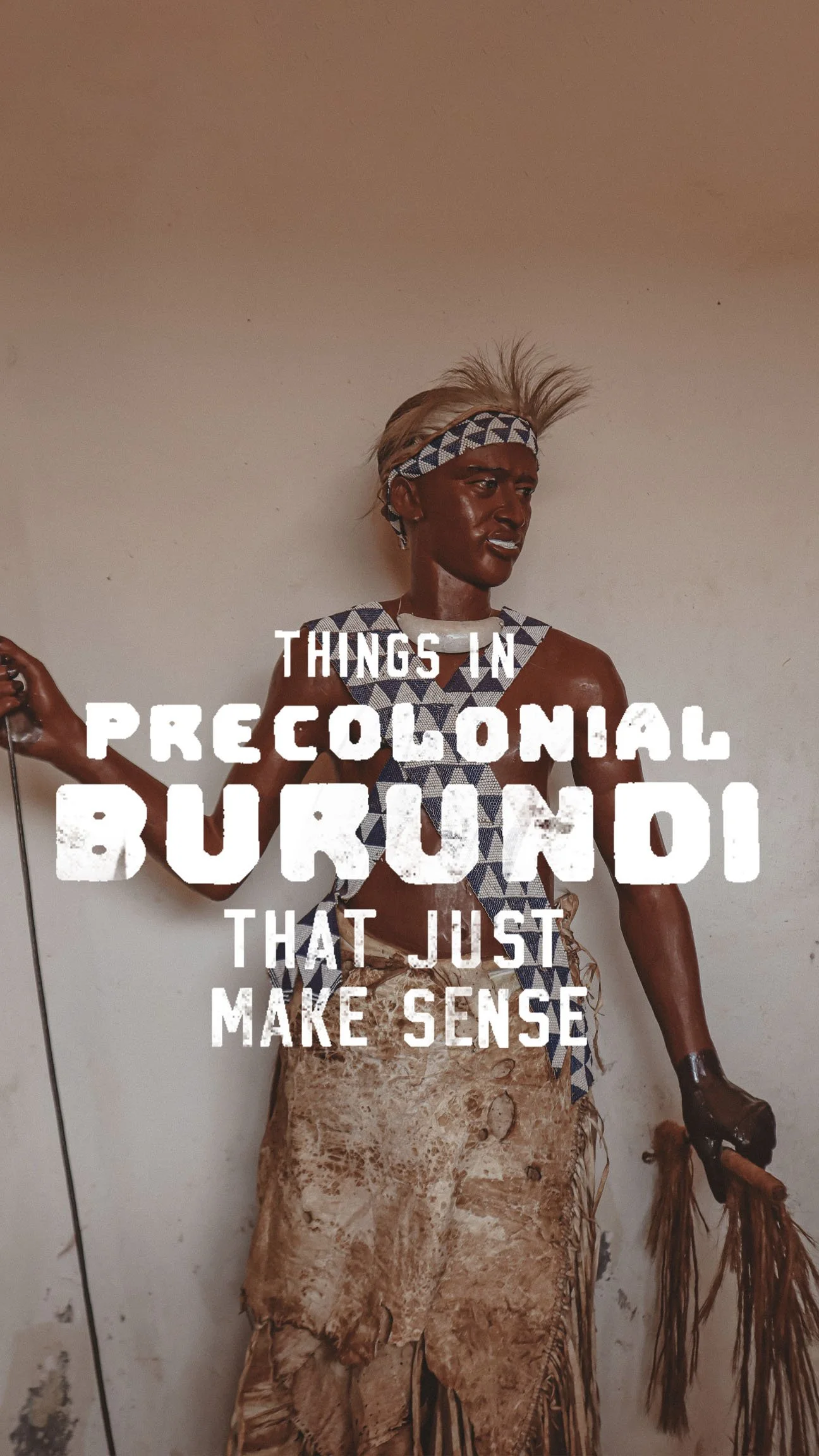

4 Precolonial Burundi

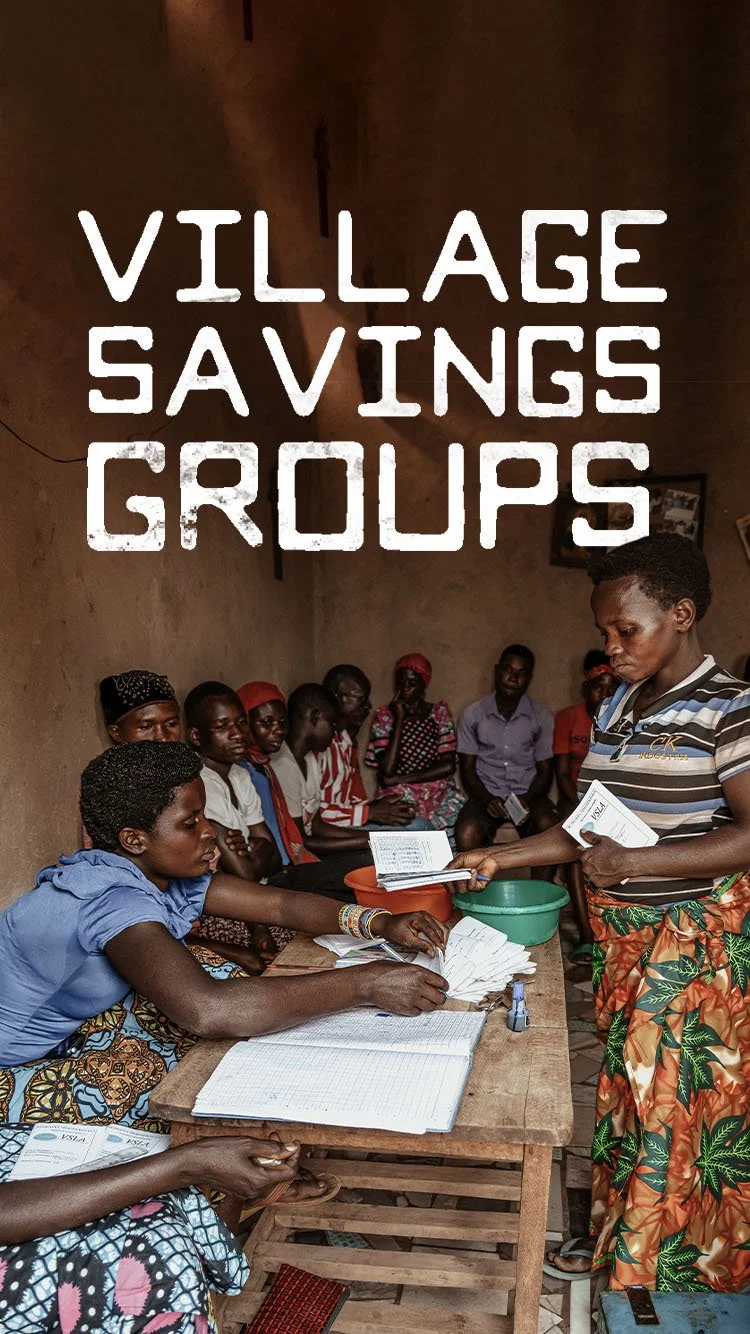

5 Village Savings Groups

6 Cow Talk

7 A Burundian Welcome

8 Fifty Million Trees

9 World’s Poorest Country

10 Burundi Fuel Crisis

11 Burundi Road Trip

12 Field Hotels

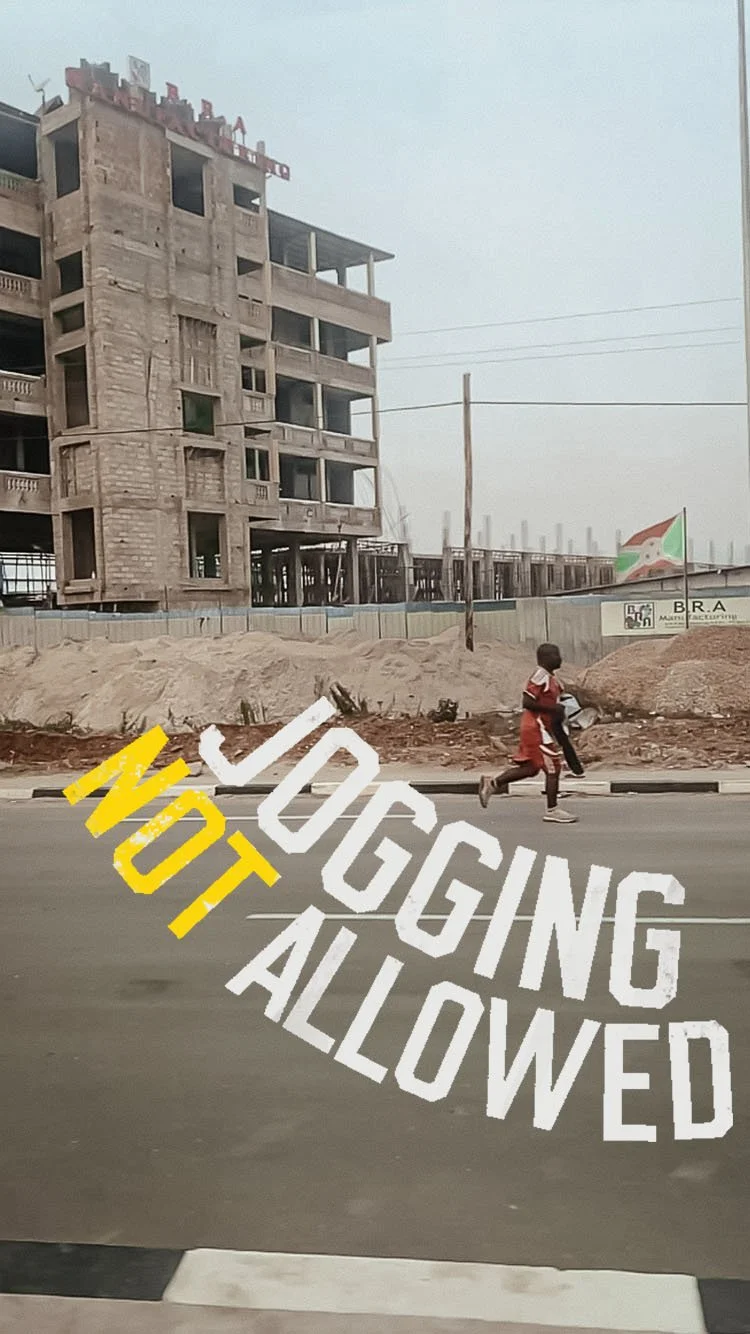

13 Jogging Not Allowed

14 A Lesson on Global Poverty

15 The Nyakazu Rift

16 Tell Deeper Stories

17 Ethical Storytelling Complexities

18 Drilling in the Congo Forest

19 Kayero Market

20 Clean Cookstoves

WELCOME TO BURUNDI

Couldn’t go to Congo

While I was in Burundi, I spent a lot of time getting familiar with Kirundi, which is a really beautiful Bantu language. One thing that stood out to me was how many of their compliments and greetings were all cow related.

“Have cows and children!” (Urakagira inka n’ibibondo)

“That guy is all cows in the field.” (Inka n’imirima)

“You have the eyes of a cow. Beautiful.” (Amaso y’inyana)

I had to confirm with my friend Emile whether I was understanding these phrases correctly. One thing is for sure. Having cows in Burundi is a very big deal in terms of your status. Cattle is wealth. It’s one thing to afford a cow, but once you do, you’ve also got a natural source of fertilizer for your field.

I love languages, and I love that there’s always so much more to switching languages than just translating sentences. The variations in how you compose thoughts and ideas result in different ways of seeing the world.

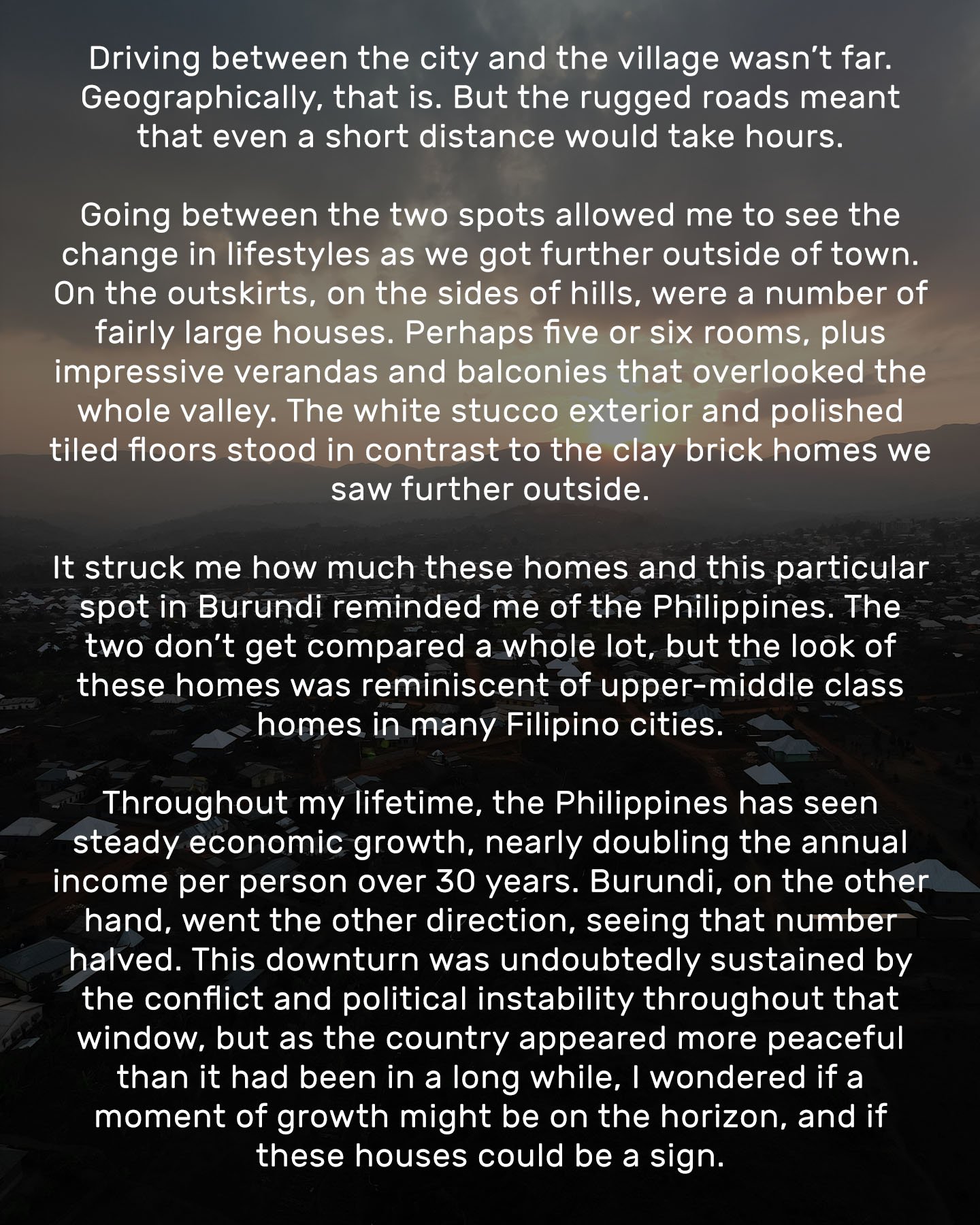

Road Tripping Burundi

Burundi is a fairly small country, which allowed us to see a large portion of it by driving around. We worked our way from Bujumbura at the top of Lake Tanganyika down to the tip where it borders Tanzania, then back up to the new capital of Gitega, right in the heart of the heart of the country.

You can learn quite a bit just by staring out the window, and the streets of Burundi gave us quite a bit to take in. Life in Burundi is diverse! I love how having a traveler’s eyes can render one person’s sense of ordinary into extraordinary.

Whenever I’m doing a trip somewhere like rural Burundi, my local partners arrange the on the ground accommodations unless otherwise noted. This often means I don’t know where I’m going to stay until I get there.

Cell signal, Wi-Fi, hot water, electricity are all question marks until I get there. Some places I’ve stayed at were camping. Others were surprisingly cozy.

What I love about these field hotels, especially the ones I stayed at on this trip in Burundi, is that the people running them cared for them with such pride.

the people of Burundi

There’s nothing quite like being welcomed with unbridled East African enthusiasm.

I really mean that. I’ve experienced this a few times now: walking into a village only to be met with makeshift drumbeats, songs, claps, ululation, and palm fronds. It’s an unbelievably life-giving experience.

To show somebody ‘welcome’ or ‘karibu’ in Swahili isn’t just a formality. It’s fully celebrating their presence. Their existence.

I know so many people go through life feeling unseen. I think we should at least be open to trying to show people over-the-top enthusiasm over the fact that they exist.

Starting a shop like this takes an investment, and most women in Burundi don’t have access to that capital, or even to a bank that could lend them the money to get started. But she found that support in her community through a Purpose Group. Now her shop has a little bit of everything and she’s not done. She hopes to further expand her shop in the near future.

storytelling work

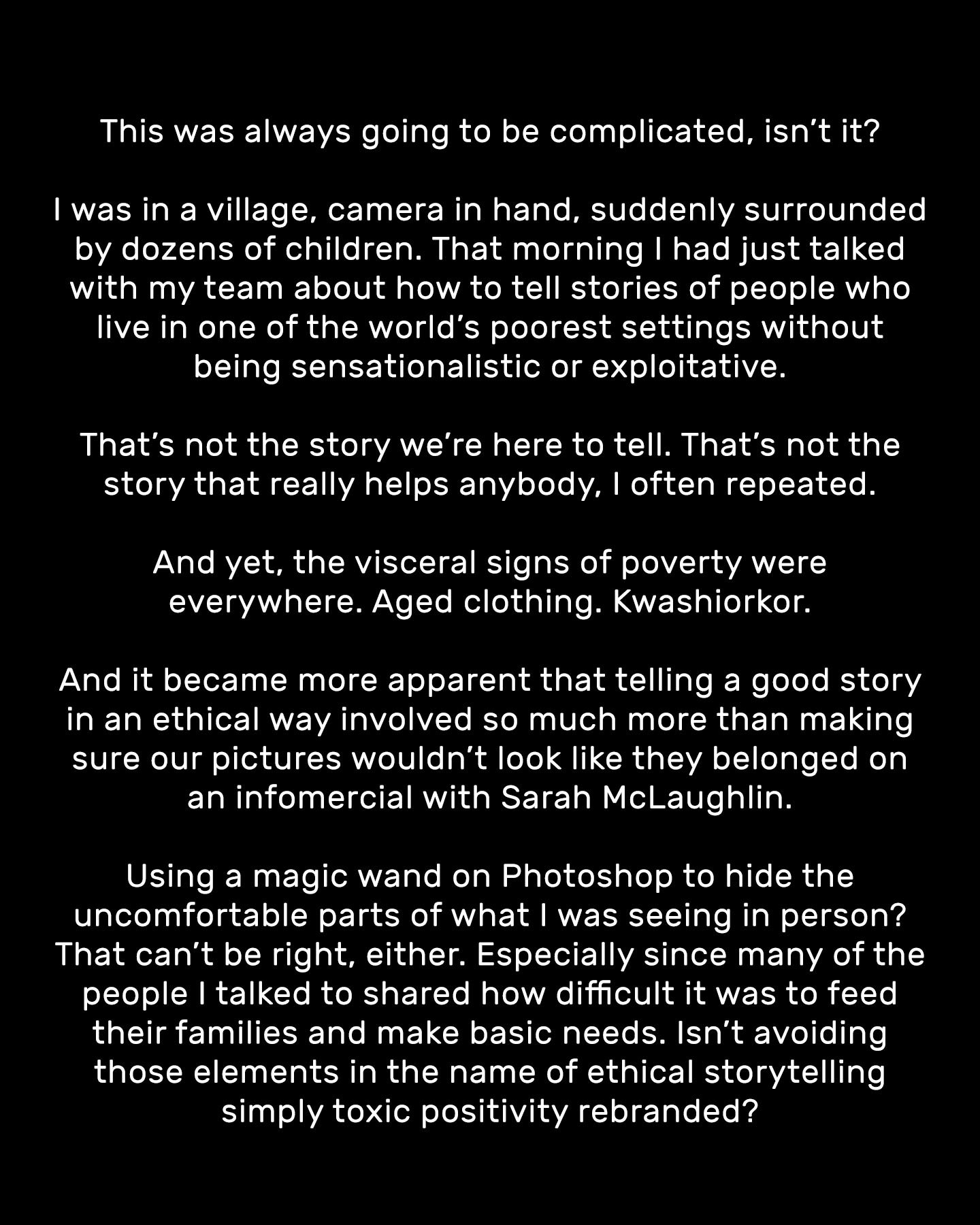

Ethical storytelling is one of the biggest things I’m passionate about. Storytelling is powerful and can shape the way we see the world, but without a conscious approach, it’s a little too easy to create unintended harm.

Being on an actual storytelling trip always highlights the way it’s complicated. You want to portray what you’re seeing with honesty, but not in a way that perpetuates harmful stereotypes and tropes.

I think one of the most important things to remember is that the process of learning is never over. You always want to be open to the likelihood that you can do things better, that there are things you’ll want to course-correct. Perhaps the easiest way to cause harm when storytelling is to think that you’ve reached a point of immunity.

But when you truly listen to the people who share their stories with you with the intent of having them spread to the world, both the stories they tell and their feedback about your handling of the stories, you stay open to that necessary, constant improvement.

on poverty

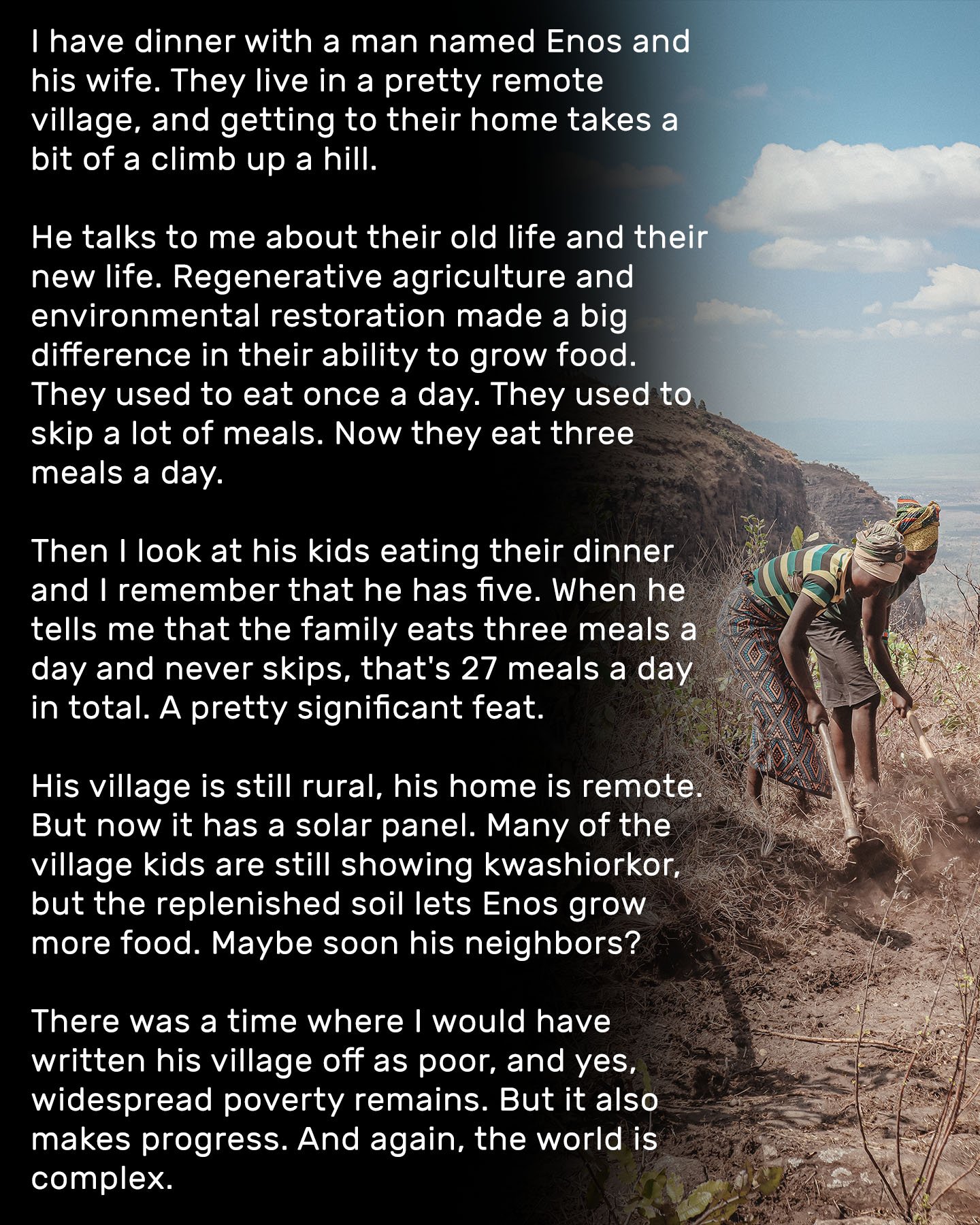

One of my more memorable encounters in Burundi was with Enos and his family. Burundi was recently named the most food insecure country, and Enos’ experience was typical. He and his kids would eat one meal a day, usually maize or spinach without much variety. Pretty frequently, they would have to skip meals all together.

Now they eat three meals a day. As someone who has never had to skip meals, that is so easy to take for granted. And when you consider that he has a total of seven mouths to feed, this becomes even more impressive.

When you have an impression of poverty that’s based on stereotypes, it’s easy to start thinking of it as something inevitable. Inescapable. But Enos shows us that this isn’t the case. Things like this are happening every day.

Are you familiar with village savings groups?

In many rural villages, banks don’t operate. With nowhere to save money, borrow loans, or invest in a community, these villages can’t make strides against poverty. But village savings groups change that by equipping communities to become their own banks.

This is an increasingly common practice, especially around Africa and South Asia. Each organization runs them slightly differently, but I’m quite partial (and biased!) towards Plant With Purpose’s Purpose Group model that pairs these activities with land restoration and environmental education.

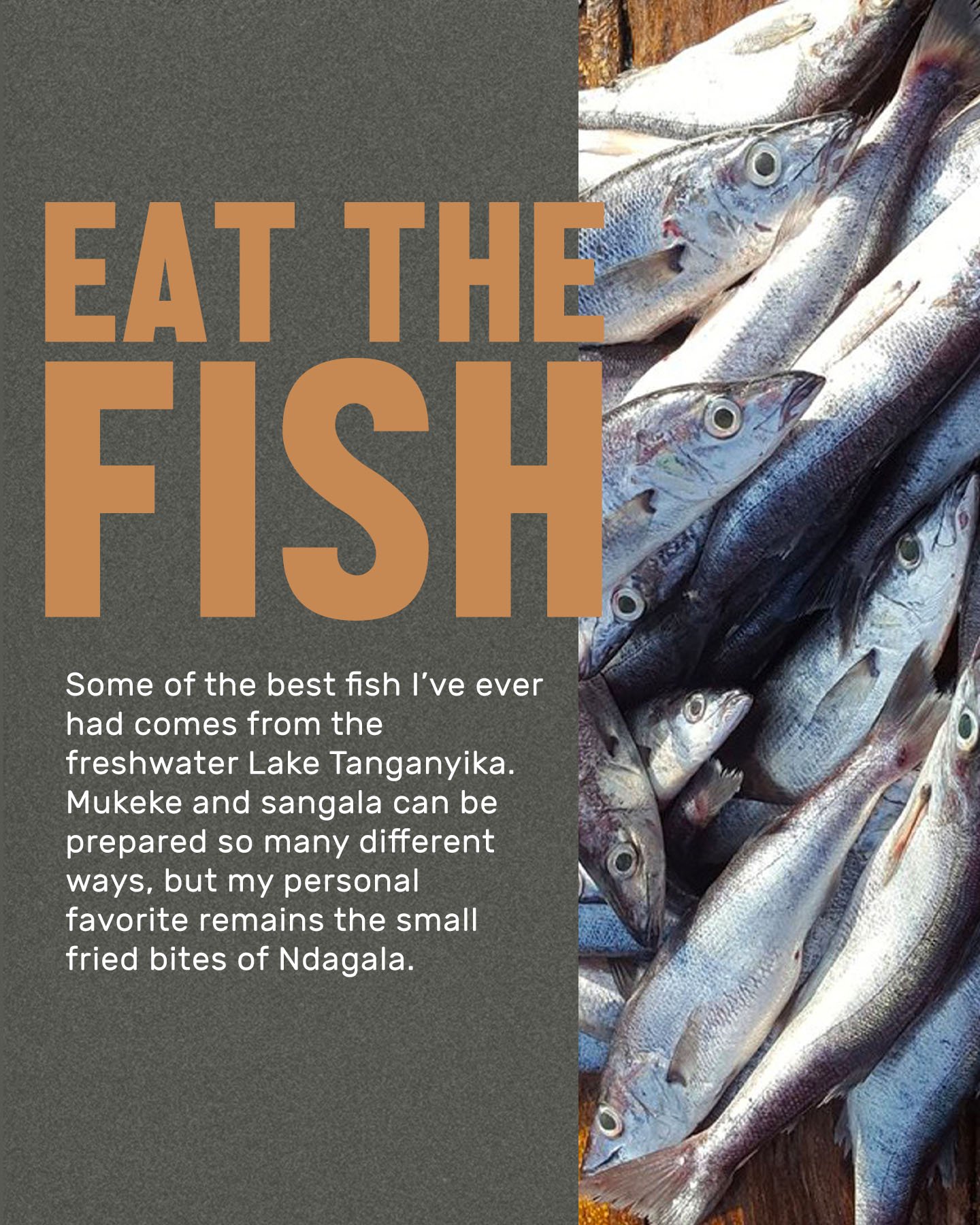

grow your own food

This is the kind of life we used to all have, the life where we grow our own food, and use the market to buy and sell for income and to fill in the gaps.

This is still life for about a billion people, but these are also the people most afflicted by poverty and climate change. This may not be the life all of us live anymore, but our decisions still have a big impact on those who do.

I’ve always been a believer that if you want to get to know the heart of everyday life in a community, head to the market. In a lot of places that means the grocery store or supermarket but in settings like rural Burundi, that’s also an open air market where goods are sold by the hands that planted them.