Why we need a sense of wonder

I arrived in Zambia via a small plane operated by British Airways. The amount of time it took to fly to Livingstone from Johannesburg was short. What felt equal in length was the amount of time it took for all of the passengers to clear customs. Since I sat towards the back of the plane, I ended up having to wait at the back of a long line.

Years ago, Zambia had dealt with a terrible outbreak of yellow fever. As far as I know, it’s still the strictest country when it comes to making sure you’ve been vaccinated prior to arrival. While I was in Johannesburg, I had to track down a clinic that offered the vaccine so I could be approved to enter Zambia. They gave me a small yellow booklet, about the size of my passport with a single stamp that assured I had been inoculated. When the line finally moved ahead so that it was my turn, a customs agent investigated the book and printed an impressive looking visa for me to enter his country, a colorful sticker that occupied a whole page. Of all the countries I had represented in my passport, Zambia left the most stylish mark.

Of course, that sticker wasn’t terribly representative of Zambia. It lacked a lot of infrastructure, as I would soon find out. A driver from the guest house I had booked appeared in uniform, holding my name on a placard. I climbed into his micro-bus, and we began the half hour drive into town.

On the way in, I noticed a lot of open air markets, and a lot of neighborhood settlements that might have resembled South Africa’s townships if not for the fact that they were far less crowded. Kids playing with each other in wide open fields was a fairly common sight, and in many ways, the popular images of Africa in the Western imagination might have been more true for this part of the continent than any other place. The dirt was a vibrant, copper red, even redder than the dirt in South Africa. It was also fine and dusty, and seemed to distinguish Zambia as its own entity. It was a colorful country. The redness of the dirt was complemented by some of the brightest, greenest brush I’d seen.

I wasn’t sure what to make of the name of the guest house I had reserved. Fawlty Towers. When I arrived there, though, it appeared that I made a pretty good decision. The rooms were clean and comfortable. The downstairs lobby resembled a typical traveler’s pub I would find in books. Plus, everybody who worked there was extremely friendly. In hardly any time I was on a first name basis with my driver, who I asked about a chance to go to a safari. He introduced me to another lady who worked at the hostel, and before I knew it, I was booked to spend at least one day in Chobe National Park. The park, which was about an hour away in neighboring Botswana, promised more elephants per acre than anywhere else in the world.

In the afternoon, the hostel served pancakes, which to me were actually crêpes. I dressed mine up with lemon and sugar, and met some of the other visitors. The guest house hosted all kinds of people, from the Zimbabwean pastor I shared a room with, to the Swedish UN worker, to a few British families working for various aid agencies and missions.

At the end of a full day of travel, I figured all that the country had to offer could wait for the next day. I put my things away in my room, and took a book down to the pub. After being given a pint of Mosi, the iconic Zambian beer, I sat down underneath the television to read for a few hours until it was dark.

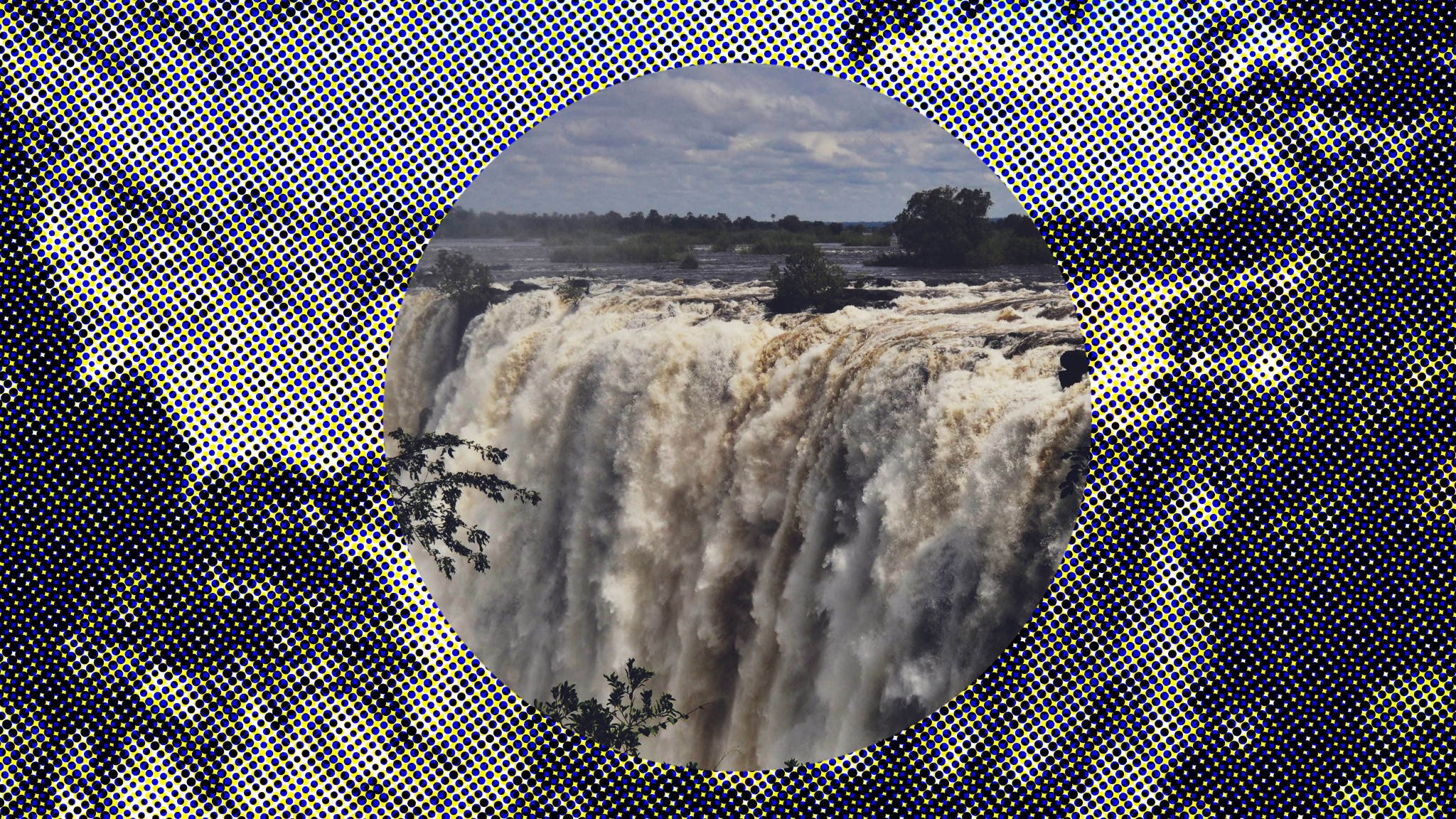

The next day, I took the bus over to the main draw of Livingstone– Victoria Falls. Mosi oa Tunya, it was dubbed. The smoke that thunders.

In pictures, the waterfalls looked like they fell upwards. The white “smoke” created by the gallons of water crashing into the pools below seemed to go twice as high as the waterfalls. From the photographs taken from airplanes, it looked like somebody had chiseled two edges of the earth apart, and out of the gap rose white misty stuff that filled the earth’s core.

The bus dropped us all off at the entrance to Mosi Oa Tunya National Park and the first thing that I noticed was neither the massive waterfall or any of the rich vegetation that surrounded it. Actually, I wasn’t anywhere that you could see the waterfall, and the deep greens of the jungle were overshadowed by something else.

Monkeys.

The whole park was occupied by hordes of baboons, and these creatures were unmistakably terrifying. They roamed about the park, uncontrolled and unbothered by the hordes of people at its entrance. It seemed pretty clear that they had gotten used to the presence of human visitors, and weren’t intimidated in the least. If anything, they saw humans as potential carriers of food.

The adult baboons were about the same size as most adult humans, though they preferred to hunch over and walk on fours when given the chance. Their appearance made it clear that they were physically strong, with hard, lanky, limbs. Not to mention some of the ugliest pink butts out there. A lot of them looked like their butts had the sort of diseases we don’t like to talk about.

One group of tourists all let out a sound of surprise as one of the baboons walked towards them. He had no reservations about leading two other baboons right through a circle of people. All of the park visitors stepped back slowly.

I took out my camera and got some good pictures thanks to a long telephoto lens. Some of the baby baboons were present, and they were the most fun to watch. I kept a tight grip on my camera, which I soon learned would be necessary.

At the trailhead, where I was about to start walking, a group of tall, young, white visitors peered off the path and towards a tree, where there was a baby baboon going after an apple. As the baboon went for the apple, one of the tall guys reached over and snatched whatever the baboon had been holding previously. It was a GoPro camera.

All of them cheered when the camera was finally recovered. One of them looked at me and told me “we’ve been trying to get that back for half an hour,” in a Norwegian accent. “It’ll be worth it though. The thing was recording the entire time.”

I made my way towards the trailhead, which promised a two mile hike down to the pool where the waterfalls crashed. From everything that I sensed and heard, it would be a really beautiful trek.

•••

Overhead, the trees were as thick as ever and they provided a refreshingly cool respite from the mild heat that blanketed Southern Zambia that time of year.

I got a strange rush of excitement at the fact that I had already been blown away by the monkeys and the vegetation, the deep greens of the leaves and the vibrant red of the dirt, and I hadn’t even gotten to the park’s main draw– the world’s largest waterfalls.

I realized that this was a common mistake that a lot of people make when on their way to see landmarks: being so enthralled and tunnel visioned towards a place’s crown jewel, that they miss out on the rest of the beauty at hand. And man, what I saw so far was gorgeous.

For the next two miles, I encountered nobody, except for one baboon who stared me down for a while before moving on. In some ways, this gave the hike a bit of an eerie feel. But it also felt serene and freeing, to know that I had escaped the confines of structure to experience these sights and smells on my own. It was a spiritual experience that I wouldn’t quite have the words for.

I found myself relating to one John Muir quote after another.

“Every hidden cell is throbbing with music and life, every fiber thrilling like harp strings, while incense is ever flowing from the balsam bells and leaves. No wonder the hills and groves were God’s first temples.”

The wildlife I encountered on this hike alone was breathtaking. Every now and then, a bird would fly by, one with one of the most vibrant blue coats and yellow shading underneath its wings. I had never seen that sort of bird before, and I had no idea what bird it was, but it was impressive. I made note of these bright red flowers that accented the green brush alongside the trail. They seemed to grow everywhere around Zambia. I bent down to take a picture. I figured they might remind Teacher Magret of her home on the other side of the Zimbabwean border.

There was something awe inspiring about this walk towards the water. I realize so much of what we try to do as humans is to try to be able to explain, describe, and predict things that are bigger than ourselves. I guess it probably gives us some sense of security or something. The thing is, we’ll never be able to fully get our heads around life, the world, or God. I think it’s a good thing to have deep convictions, and its practically impossible to live without them, but it’s when we get so caught up in wanting to explain and predict and prove ourselves right that all of our worst sides come out. Political vitriol. Religious zealotry. Us versus them ways of thinking. And those quickly unravel into moments of violence or episodes where we’re no longer able to be civil to each other.

I’ve found wonder to be a good antidote to that. Taking the time to be astounded by something will speak to our deepest convictions and affirm them, all while flooding us with humility and an appreciation for the vastness of God and his world. The philosophies and ideas I find the most convincing come from the minds that haven’t quite recovered from seeing how spectacular it all is.

I got to the base of the pool and it was serene and beautiful. It looked calm enough to swim in, but the water was freezing. I still managed to soak my feet and stare up at the bridge that went from one side of the carved out gorge to the other. This was the bridge that connected Zambia to Zimbabwe, and I knew I wanted to be there by the end of the day.

After spending some time soaking in the base of Victoria Falls, I decided it would be time to make my way towards the main spot to view it spot on. Getting to the right spot would mean backtracking to the point where I had started my little hike, before climbing up a paved footpath that led to the top of the gorge where the waterfall began.

It was just as beautiful walking in the other direction, and I again encountered the bluest birds and the reddest flowers. The walk back went by surprisingly quickly. Along the way, I found myself staring down a baboon in a close encounter while I was still by myself. That wouldn’t be the scariest experience of the day, though.

Once I had gotten back, closer to the park’s entrance, I found the path that led to the top of Victoria Falls. There were a lot more people along this trail, which wasa series of cobblestone steps at uneven heights.

I knew I had started to get closer when I encountered green painted stones inscribed with the words, DANGER! Stay on the trail. Just as soon as the painted stones appeared, I became able to hear the thundering crashes of the water, which in reality was present the whole time, but I was finally able to hear it amplify. As I came within a half mile of the waterfall, I began to feel water drops come down on my skin. It was a bit like a drizzle.

I had been forewarned by guidebooks at the guest house that the waterfalls were so forceful that walking by them felt like being in a heavy rainstorm. I underestimated how accurate that description would be. By the time I made it within a few hundred feet of the prime viewing point for the waterfall, it was like being in a torrential downpour. The water drops that struck my skin were fiercer and everything around me was drenched.

I had a plastic poncho with me that I had put on, but I soon found out that it was terribly inadequate, and didn’t even keep me completely covered. I coughed up the five dollars that nearby vendors were charging for rental ponchos.

I climbed the last of the steps.

When I got to the top, I saw one of the earth’s most impressive sights. The waterfalls were vast. Powerful, too. I don’t think I’d ever seen anything in nature come across with as much strength as I saw from the crashing of the falls. Standing in the midst of the “smoke that thunders” I realized that smoke was hardly the right word. It was a very heavy shower.

I took out my camera and got a few good pictures. The place was magnificent, and I was standing in the very best spot to view the waterfalls. Well, almost.

I came to a bridge. It was a skinny bridge made out of metal that had inevitably rusted from the constant shower it was exposed to. It led to the point that was dead centered across the middle of the waterfall. The bridge was narrow, and most people weren’t bothering with it.

A park ranger caught me eyeing it.

“If you’re going to use that bridge, make sure you’re the only one on it. It can only take one person at a time.”

I decided to go for it.

I stepped onto the bridge, my feet immediately making a resonating clang against the hollowed out metal. Where my feet were, the walkway of the bridge seemed barely wide enough to accommodate both of them side by side.

As I continued to walk ahead, I realized that this bridge was way more intimidating to walk across than it looked like from a distance. The structure of the side rails allowed for very large gaps, large enough for an adult to slip through if he lost his footing. That also seemed to be a possible outcome. The constant wetness had made the bridge an extremely slippery surface, and I was surprised nobody had thought about that when designing it. I slowly slid my feet across one at a time.

A park ranger continued shouting instructions to me from the other side, but it was hard to hear him with the thunder of the waterfalls.

I took steps slowly, even though I wanted to get off the bridge and onto the solid ground as soon as possible. The constant spray of water on my face only made things more difficult.

I made it to the middle.

I looked up and saw the waterfalls from this vantage point and it was so phenomenal it made everything worth it. Of course, there would be no using my camera this time around. It was in my backpack, tucked tightly underneath the poncho, and I wouldn’t be fidgeting with that while on this slippery bridge. Besides, the difference between that photo and the one I took earlier wouldn’t be that obvious in photographs. It was only in person that you could tell the view from the bridge made all the difference. It was as if the treacherous walk forced me to turn on all my senses for my own protection, and I was rewarded with the scent of the freshest water, the coolness of the water, the sight of the rampaging white crash, and its glorious roar.

Even though I couldn’t have taken a very long pause on that bridge, a freeze frame of that moment remains permanently set in my mind. I suppose that’s what the unfamiliar and the unsafe does to us. It slows down the time and brings our senses to life.

On the other side was the start of another trail. This one promised to be shorter and since I had undergone the trouble of crossing the bridge, I figured I might as well follow. Only after walking several yards away from where the bridge was, the spray of the water began to quiet down, growing into a subtle background noise. The spray grew lighter, into a mist, until it was hardly felt at all. If not for my recently enlivened senses, I might have figured it to have completely ended.

The trail sent me back behind the waterfall, up to the Zambezi River, before the 350 foot drop.

Along the sides of the river were plenty of locals hanging out and resting, and I decided to join them.

It was remarkable how serene the river was at this point, when it’s sudden downpour was not too distant. I followed it to a point where I could access the rushing river easily and walked beside its stream. It was the Zambezi, one of the world’s most powerful rivers, but at this point along its path, it was subdued, it’s strength stirring quietly underneath its top.

Serene as the area seemed, I didn’t dare get into the water, knowing that it was much stronger than it appeared and would lead to an unsurvivable drop.

I made a note of how much time slowed down this day as all of my senses were fully focused on whatever was in front of it.

Whether we like it or not, we move through time, and there’s no stopping its march. All we can do is simply come fully alive each day so that throughout its course, we miss out on nothing.

•••

South Africa had taught me the value of not rushing through time, of learning how to appreciate the present for what it was, and of experiencing God through stillness. It had helped me to see the importance of being present for people, with people, and to be patient with wanting to see things change.

Here in Zambia, I was getting a hands-on course on how to absorb my surroundings and be “in the moment” like people say.

At the end of that day, I would find myself at a pizza parlor founded by some Italian NGO workers. It was unexpectedly phenomenal pizza. I took the time, over my pizza and my second pint of Mosi to celebrate the day’s events. Before it had ended, I had made it into Zimbabwean territory by foot, walking across the border, and enjoying the Falls from their other side. The next day, I had a safari to look forward to.

I knew that the trip to Zambia had not been in vain. If nothing else, I had a deeper appreciation for being able to sense and enjoy life within a single moment. Perhaps that’s just one of the reasons travel can be so good for a person.